Students of the United States Colored Troops and the Battle of New Market Heights should at least recognize the name of Medal of Honor recipient Alfred B. Hilton. That they may know relatively little about him results from a scarcity of printed literature about his life. This biographical essay will reduce some of that shortage while advancing the thesis that Hilton’s Civil War experience likely provided him a sense of personal satisfaction and fulfillment denied him while living in rural Maryland.

The facts of Hilton’s life can be summed up in relatively succinct fashion. He was born a free man in the late 1830s to parents who had been enslaved persons in their youth. In 1860, Alfred was a 23-year old laborer, living and working with six siblings and his 60-plus year-old parents on their mortgaged farm, in the Hopewell Crossroads area of Harford County in central Maryland.

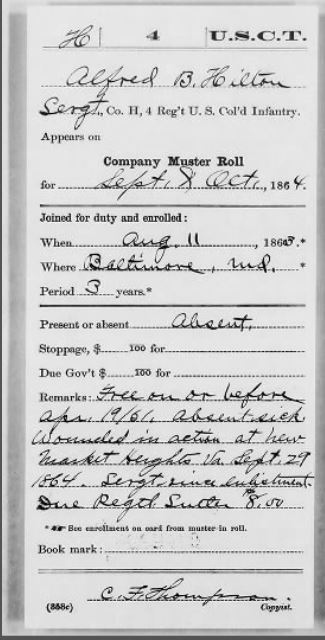

Alfred Hilton’s life changed drastically in August 1863, when he, brothers Aaron and Henry, and several free neighbors enlisted at a recruiting station for African Americans in nearby Havre de Grace. Taken almost immediately to Baltimore, and mustered into Company H of the 4th United States Colored Infantry, regimental officers immediately designated Alfred as a sergeant.

The fully organized regiment departed Baltimore by steamer on September 29, 1863 (exactly a year before the Battle of New Market Heights) and sailed down the Chesapeake Bay to Yorktown, Virginia, to receive additional training. For eight months the regiment continued its training but mostly performed fatigue duties and participated in an occasional foray in the general area.

With the onset of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s aggressive new strategy in the spring of 1864, the United States Colored Troops’ (USCT) contributions to the war effort changed significantly. On May 4, l864, the 4th USCI and several other African American units sailed up the James River to join Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler’s Army of the James in its campaign against Petersburg and Richmond. On May 15th regimental commanders detailed Sgt. Alfred B. Hilton to the post as the national color bearer. Hilton’s cohort Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood subsequently described his friend at 5’10” as a “magnificent specimen of manhood…splendidly proportioned.” Hilton’s stature also made him an incredibly imposing target for enemy soldiers.

Color Sgt. Hilton almost immediately found his fortitude put to the test. On the early morning of June 15th at Baylor’s Farm, between City Point and Petersburg, despite heavy rifle and artillery fire, he led Col. Samuel Duncan’s brigade of Hinks’ Division in clearing the rebels from the City Point Road east of Petersburg before moving farther west.

That evening, now within six miles of their objective, Hilton again fronted the brigade in a successful offensive against the Confederate Dimmock Line of earthworks, securing Batteries 7, 9, and 11. Although the division had opened up the road to Petersburg, Union authorities failed to press the initiative, and the campaign settled into siege-style warfare. The offensive efforts of African-American soldiers such as Hilton, however, had contributed mightily to the development of a new-found respect for the fighting abilities of USCT troops.

Sgt. Alfred B. Hilton’s third major charge as color bearer proved to be his last. On September 29, 1864, as the Union drew closer to Richmond-Petersburg and with Duncan’s Brigade again in the front, Hilton directed the 4th USCI in the dawn attack against veteran Confederate troops entrenched at New Market Heights. Despite intense enemy fire that Sgt. Maj. Fleetwood described as “a deadly hailstorm of bullets” that bowed men over “as hailstones sweep through the trees,” Hilton reached the rebels’ inner lines.

That he succeeded in reaching so forward a position was all the more remarkable as he had paused in the midst of the barrage to retrieve the regimental flag when its bearer went down. Official records noted that Hilton “struggled forward with both colors, until disabled by a severe wound at the enemy’s inner line of abatis.” Notwithstanding his injury, Sgt. Hilton managed to return to the regimental lines with aid from the men who relieved him of the flags when retreat sounded.

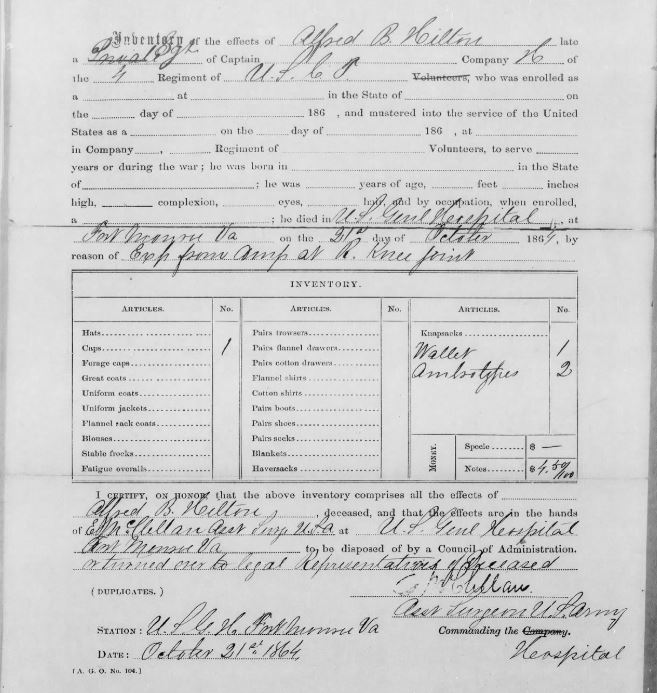

Removed from the battlefield, Hilton received treatment at the United States General Hospital at Fort Monroe, but succumbed on October 21, 1864, of “the effects of amputation of the right leg.” Buried in the hospital’s graveyard a few days later, he now rests at Hampton National Military Cemetery. Hilton’s contribution to the war effort had ended.

Comparing Hilton’s life circumstances prior to enlistment and his experiences in the military yield some interesting conclusions. In particular one senses that despite the restrictions, hardships, rigors, and discrimination that came with serving with the USCT, Hilton’s months in the military were very likely the most liberating, most satisfying, and personally fulfilling period of his life.

Life for free persons of color in rural Maryland was grim. Most worked as tenants or as laborers for small farmers, lived in crowded and dilapidated quarters, and depended on minimal economic resources to sustain themselves. As property holders, the Hiltons were perhaps somewhat better off than many of their counterparts, but nonetheless suffered many of the same hardships as their compeers. None of the members of their nine-person household (down from an initial fourteen) could read or write, and relied on a 14-acre mortgaged hardscrabble farm to eke out a living.

In 1860, Harford County freedmen comprised 15.6 percent (3,644 persons) of the area’s 23,415 residents, a number large enough to constitute a threat to the governing class. A good number of whites regarded free people of color as pariahs, individuals whose mere existence (and presumed covert activities) served to encourage the area’s 1,800-plus enslaved persons to bolt for freedom across the nearby Mason-Dixon Line. Pro-slavers watched in shock as scores of freedom seekers slipped away and as the numbers of local freedmen grew by 31% in the decade of the 1850s. Large numbers of newly arriving Irish immigrants, in particular, regarded free African American laborers as competitors, depressing wages and vying for the few full-time and seasonal jobs as farm laborers. One county resident summed up the prevailing sentiment of many whites in condemning free people of color as a “most fruitful source of mischief and disquietude.”

In assessing Hilton’s military experience, one wishes for the unattainable: that he was literate, that he had survived to produce memoirs, that he had conversed with chaplains who published in the Christian Recorder, that brothers Aaron and Henry (who survived the war) had later shared their experiences, and that Alfred had dictated letters home during the war and especially during the three weeks he was in the hospital. The usual “if onlys” of doing history!

Despite the lack of original sources, one can infer that Hilton’s resolve to join the United States army in the summer of 1863 constituted an act of defiance, an assertion of his personal emancipation proclamation, and a rejection of Harford County’s prevailing ethos.

Like many men in the USCT, Hilton’s deliverance came in many, originally unforeseen, and largely unexpected ways. Even his journey to Baltimore, likely his first experience with travel beyond the borders of Harford County, offered opportunities –literacy classes, spiritual instruction, lessons in hygiene–denied him in Hopewell Crossroads.

Most significantly, the unlettered farmhand, post-August 1863, now had a Cause, a life objective, and a reason for being – to assist in the national effort to preserve the Union and to end the accursed system that had entrapped his family and so many other people–black and white, free and enslaved–in untold ways.

Hilton’s first palpable success in his quest came the very day the young enlistee mustered in at Camp Birney. Officers of the 4th USCI immediately designated him as sergeant, providing Hilton an identity unique among his Harford County comrades. The upgrade in rank would most likely have appeared to him as a reflection of the confidence his superiors had in his maturity, his ability to command respect, and proficiency in leading others in fulfilling the regiment’s mission. Hilton would logically have considered his subsequent assignment to the coveted position as national color bearer as an affirmation of his commanders’ on-going confidence in his ability to contribute meaningfully to the accomplishment of the nation’s wartime goals.

Had Sgt. Hilton survived the attack at New Market Heights, he would have personally received the Medal of Honor, testifying to his extraordinary efforts to end to the blight of slavery, claim citizenship, and save the Union. Because of his death, Hilton received the Medal of Honor posthumously on April 6, 1865, three days before Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox and seven months prior to the official ratification of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution ending slavery. Goals accomplished.

By Jim Chrismer

August 1, 2020