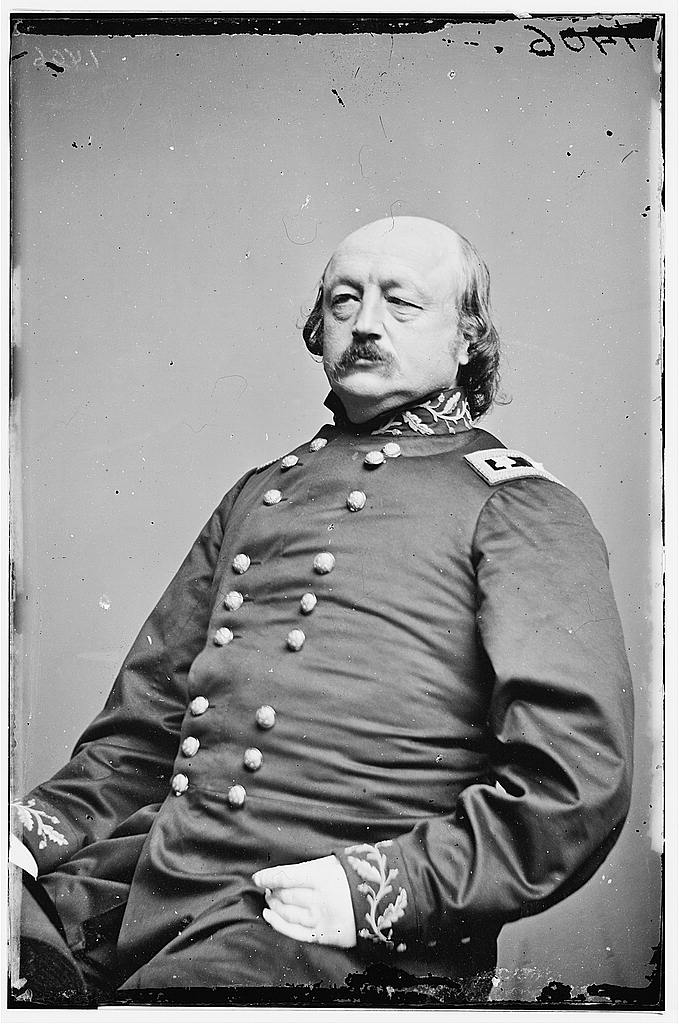

On October 11, 1864, less than two weeks after the battles fought at New Market Heights and Fort Harrison, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler produced a circular praising the efforts of the X and XVIII Corps, which comprised his Army of the James. “The time has come when it is due to you that some word should be said of your deeds,” Butler opened. Through the next several pages Butler outlined the overall operation, known as the Battle of Chaffin’s Farm, and then detailed the individual accomplishments of many soldiers in each division of each corps. In doing so, Butler recorded examples of African American soldiers, who took on command roles when their white officers became casualties. Butler’s comments discredited prejudicial perceptions against Black soldiers’ ability to lead on the battlefield.

Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, Army of the James, mentioned several examples of Black men who took command of their companies at the Battle of New Market Heights. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Third Division of the XVIII Corps, led by Brig. Gen. Charles Jackson Paine, and comprised of eight United States Colored Infantry (USCI) regiments, received well-deserved acclaim in Butler’s document. While their comrades in the First and Second white divisions attacked at Fort Harrison, the detached Black Third Division fought at New Market Heights. Battling against some of the best fighters in the Army of Northern Virginia—the Texas Brigade—Paine’s Black soldiers endured a severe test.

The Texans and several dismounted cavalry regiments to their left held a number of defensive advantages. First, they were fighting behind earthworks. This force multiplier gave them an anchored position from which to deliver devastating firepower. These Confederates also constructed two lines of abatis they placed in their front with the intent to slow any attacking force and provide opportunities to take careful aim. Also, a marshy Four Mile Creek served as a serious impediment. In addition, a signal tower above the Texans on New Market Heights helped concentrate defensive troops to the main point of attack. Finally, experienced Confederate artillery units—the Rockbridge Artillery on their left and the 3rd Company of Richmond Howitzers on their right—helped protect the flanks. It goes without saying that the USCTs received a terribly difficult assignment on September 29, 1864, at New Market Heights.

Attacking first, at about 5:30 a.m., Col. Samuel Duncan’s brigade (the 4th and 6th USCI regiments) assaulted the Texans in a battle line with the 6th to the left and behind the 4th, the two regiments slightly overlapping in the center.

The abatis did its job effectively. While a few soldiers made their way through the entanglements, up to and into the earthworks, becoming prisoners, the vast majority took heavy casualties at the obstacles. The small brigade lost over half of its men killed, wounded, or captured. The officer ranks of the 6th USCI was decimated. Company D of the 6th came out of the fight with only three of the thirty soldiers who entered it.

Examples of heroism abound in Butler’s October 11 circular. For example: “Alfred B. Hilton, color-sergeant, Fourth U.S. Colored Troops, the bearer of the national colors, when the color-sergeant with the regimental standard fell beside him, seized the standard, and struggled forward with both colors, until disabled by a severe wound at the enemy’s inner line of abatis, and when on the ground he showed that his thoughts were for the colors and not himself,” Butler noted. Hilton died from his wounds on October 21, 1864. He received the Medal of Honor posthumously on April 6, 1865.

Despite being severely wounded, Sgt. Alfred B. Hilton (4th USCI) helped keep both the national and regimental colors safe.

Photo by Tim Talbott

Unable to go any further without support, Duncan’s Brigade withdrew. Brig. Gen. Paine next ordered Col. Alonzo Draper’s brigade, consisting of the 5th, 36th, and 38th USCIs to attack. These regiments assaulted the Texans over the same ground Duncan’s Brigade attempted.

Attacking in a compact column rather than an extended battle line, Draper’s Brigade also met furious resistance. Many of the Texans had come onto the battlefield in between Duncan’s and Draper’s attacks and gathered up rifles, cartridge boxes, and took other equipment, clothes, and shoes off of Duncan’s men. The defenders were well ready. One Texan remembered he had seven rifles ready for the next attack.

Some of Draper’s soldiers were able to take advantage of the openings in the abatis created by Duncan’s soldiers, but again, the obstacles held most of them up. After what Draper referred to as “a half hour of terrible suspense” the officers and Black non-commissioned officers were able to get their forward momentum going again. Lt. Joseph Scroggs, 5th USCI, noted in his diary: “The Color bearer was killed on one side of me and my orderly Sergt. wounded on the other, two of my Sergts. killed and my company seemingly annihilated, yet on we went through the double lines of abatis, and over their works like a whirlwind.”

As with Duncan’s Brigade many of the white officers in Draper’s Brigade went down. The Confederates believed that without their white officers, the Black enlisted men and non-commissioned officers would not continue fighting. Many white Federal soldiers believed the same thing. The USCTs at the Battle of New Market Heights proved them all wrong.

Butler made particular mention of several non-commissioned officers in the 5th USCI, who took on company leadership roles: “Milton Holland, sergeant-major, Fifth U.S. Colored Troops, commanding Company C; James H. Bronson, first sergeant, commanding Company D; Robert Pinn, first sergeant, commanding Company I, wounded; Powhatan Beaty, first sergeant, commanding Company G, Fifth U.S. Colored Troops—all these gallant colored soldiers were left in command, all their company officers being killed or wounded, and led them gallantly and meritoriously through the day.” Each of these soldiers also received the Medal of Honor on April 6, 1865, for their courageous leadership at New Market Heights.

Sgt. Maj, Milton Holland (5th USCI), born enslaved in Texas fought against Texans at the Battle of New Market Height. Holland received mention by Butler for his leadership on September 29, 1864. Image in the public domain.

In addition, Butler also credited 1st Sgt. Edward Ratcliff, Co. C, 38th USCI for his leadership. 1st Sgt. Ratcliff, “thrown in command of his company by the death of the officer commanding, was the first enlisted man in the enemy’s works, leading his company with gallantry. . . .” Ratcliff, too, received the Medal of Honor on April 6, 1865.

Despite these examples of leadership ability, commissioned officer promotions for Black men in field regiments remained rather rare throughout the remainder of the Civil War. For every James Monroe Trotter, who was finally mustered as a 2nd lieutenant in the Black 55th Massachusetts Infantry in June 1865—after the fighting had ended—there were many more Milton Hollands, James Bronsons, Robert Pinns, Powhatan Beatys, and Edward Ratcliffs, who had shown they could lead as officers but were not provided the opportunity because of the color of their skin.