Pvt. William Empson’s grave at Hampton National Cemetery has his name spelled incorrectly. Photo courtesy of Wisteria Perry.

One wonders what thoughts flooded the mind of Pvt. William Empson as he traveled down the James River by hospital boat from the battlefield of New Market Heights to the United States General Hospital at Fort Monroe, Virginia.

Among the many things that must have weighed on him, he likely considered his chances for survival. It did not take much combat experience for a soldier of that period to learn that a gunshot wound to the abdomen often proved fatal. By September 29, 1864, Empson had experienced combat first-hand. Whether participating in excursions on the James and York River peninsula to free enslaved people and fight guerrillas, battling Army of Northern Virginia foes at Baylor’s Farm and Petersburg’s Dimmock Line on June 15, 1864, or enduring Confederate shells while working on the Dutch Gap Canal project, Pvt. Empson had “seen the elephant” and knew what lead and iron could do to the human body. He knew what wounds were treatable and survivable, and those that usually were not. His excruciatingly painful wound was one that surgeons of the time could do little about. Knowing this must have caused him considerable stress.

Pvt. Empson also probably thought about his family. As tons of letters clearly bear out, family was important to most Civil War soldiers, no matter their race or background. It probably did not matter if Empson’s family was nuclear, extended, or dispersed, or whether they were living at the time or had passed long ago. Memories of times with them could not help but come across his mind. As is too often the case with United States Colored Troops soldiers, we know little about Empson’s life and family before his enlistment on August 13, 1863, at Smyrna, Delaware as a 28-year-old.

Census records help a little. It appears that the Empson family were free people of color as early as 1840. William Empson appears as the head of household of a family of four in that year’s census in the St. Georges Hundred district of New Castle County, Delaware. Those four individuals appear to be William Empson, Sr., his wife, son (William Empson, Jr.), and a daughter. The boy and girl were both under ten years old. Unfortunately, the 1840 census only provides the name of the head of household, which of course, limits connections to future census records.

In the 1850 census, it looks like William Empson, Jr. and some family relations lived in the household of a white man named James R. Statts (or Stutts) and his family in St. Georges Hundred. Listed are Ann Empson (27), William (17), Andrew (14), Mary (1), and a John Watson (20). If the census taker recorded her age correctly, Ann Empson is too young to be William’s mother. Andrew and Mary were probably William’s younger siblings. Another Empson family lived in the same district with Isaac Empson as the head of household. Isaac Empson was perhaps William’s uncle, but that is uncertain.

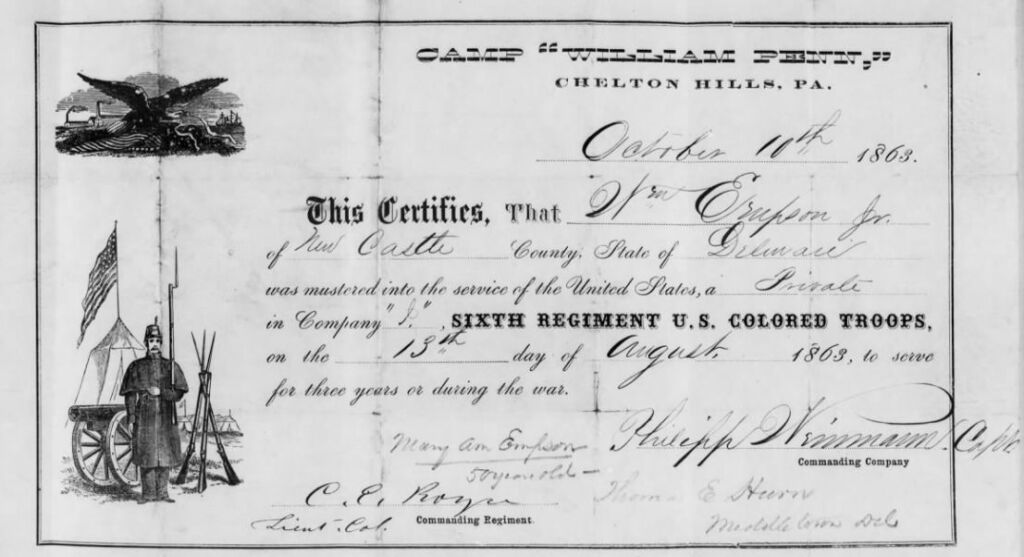

This document, which certified Pvt. Empson as a United States soldier is included in his compiled military service record. Courtesy of Fold3.com.

While there are some William Empsons who appear in the 1860 census for St. Georges Hundred, Delaware, none come close to fitting into Pvt. Empson’s age range. Was he working out of the area in 1860? Did the census taker perhaps miss him? It is unknown. However, by the summer of 1863, William was included in a draft registration for New Castle County. Along with his brother, Andrew (who apparently did not serve during the war), William is noted as an unmarried laborer and native of Delaware in the draft registration’s enumeration.

Along with thoughts of his ultimate fate, and recalling past times with family, Pvt. Empson must have also contemplated how he had come to this place in his life. His compiled military service records help fill in some of that information. As mentioned above, Empson enlisted on August 13, 1863. However, he was not a volunteer. Apparently among those pulled from the draft registration list, Empson made his way to nearby Smyrna, Delaware, where he joined Company I, of the 6th United States Colored Infantry as a draftee.

In what was yet another example of racial injustice during the American Civil War, Black men who ended up drafted, despite not receiving the benefits of citizenship, must have felt particularly galled who found themselves in those circumstances. Regardless of Empson’s political thoughts on the situation, he went when the United States called on him.

Sometimes incorrectly noted as Emerson in his service records, and listed as 28 years old with a “black” complexion, Pvt. Empson’s service records are not real clear on his height. It is difficult to tell if he was only five feet and a half inch tall, as is stated, or if that is supposed to be interpreted as five feet six inches tall. Unfortunately, Empson’s occupation at enlistment is again noted as “laborer,” like on his draft registration, and thus gives us little insight into how he made a living before enlisting.

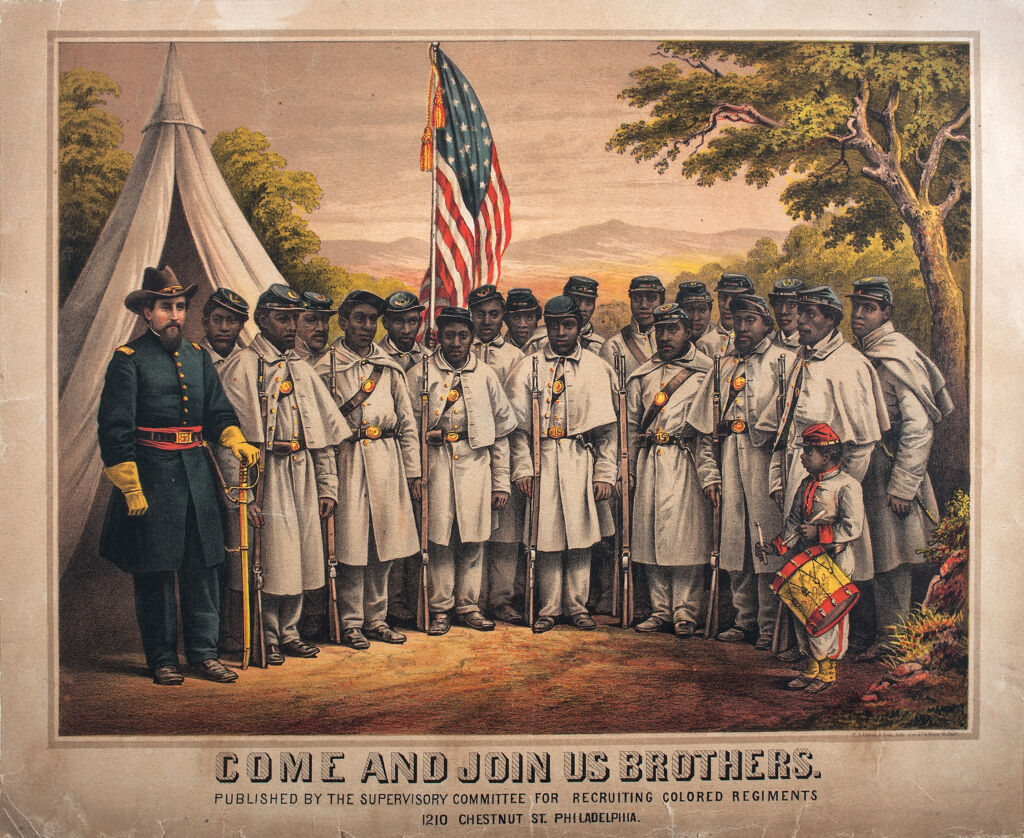

Camp William Penn served as a USCT recruiting and training center near Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Image in public domain.

Officially mustered into United States service on September 11, 1863, at Philadelphia’s Camp William Penn, a large recruiting and training center for USCTs, Pvt. Empson’s early enlistment was apparently not without its ups and downs, as he was charged for losing or damaging pieces of his equipment. However, he was always present for duty. In Pvt. Empson’s service records is a unique document from his time at Camp William Penn. It is a certificate dated October 10, 1863, signed by his company captain, Philipp Weinman, and apparently served as proof of his service in the 6th USCI. Also noted on it, probably at a later date, is “Mary Ann Empson 50 year old” and then “Died Sept 10 1865.” Were these notations information about Empson’s mother and associated with a pension application?

Pvt. Empson and his comrades in the 6th USCI, along with the 4th USCI, both in Col. Samuel Duncan’s brigade, were the first wave to assault the Confederate line at New Market Heights early on the foggy morning of September 29, 1864. Battling the famous Texas Brigade, who had several force multiplier advantages, including two lines of abatis, earthworks, artillery support on each flank, and a signal tower that provided information on where to concentrate its defensive manpower, Duncan’s Brigade took heavy loses, losing over half its force killed, wounded, or captured. During the battle, the 6th USCI’s Lt. Nathan Edgerton, Sgt. Maj. Thomas Hawkins, and First Sgt. Alexander Kelly all eventually received Medals of Honor for performing courageous acts. With many of the white officers killed and wounded, the Black noncommissioned officers for the 4th and 6th USCIs took on leadership roles and helped withdraw those soldiers still on their feet from the field.

Removed from the battlefield by ambulances and placed on a hospital transport boat at Deep Bottom Landing, Pvt. Empson and hundreds of other USCTs traveled down the James River to hospital facilities to receive treatment. He died on October 2, 1864, at the U.S. General Hospital at Fort Monroe.

Finally, one wonders if Pvt. Empson thought about his legacy. Did he feel that he had contributed to the United States war goals of abolishing slavery and reuniting the country in order to make way for Black citizenship and the beginnings of a “new birth of freedom?” Sadly, Empson’s name—like several other New Market Heights USCTs—is misspelled on his tombstone that now marks his final resting place at Hampton National Cemetery. Without doing some research, one would never know just by looking at his grave marker the important historical events that Pvt. Empson participated in and how he sacrificed his life to create a “more perfect Union.” Hopefully, Pvt. Empson would be happy that he is indeed being remembered and that we appreciate his service and sacrifice.