Every now and then a little serendipity smiles upon the researcher. I’ve been researching and writing about United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers who fought at the Battle of New Market Heights for several years now in effort to know more about this often overlooked battle and its significance to American history, and to gain better insight to the men who fought there.

Being that so few of the battle’s Black soldiers left letters, diaries or journals, or memoirs, it requires searching for information to tell their stories though other sources like pension records, which are often not easily accessed without research trips to the National Archives in Washington D.C. White USCT officers certainly left more accounts, and their personal information is almost always rather easy to locate, but even these men sometimes present challenges. So, this process is often slow, time consuming, and sometimes frustrating, but in the end, it is always rewarding work. Even finding the smallest scrap of new information adds toward making the battle’s picture a bit more complete.

Recently an individual contacted the Battle of New Market Heights Memorial and Education Association via email after reading our website. He mentioned that his parents were buried in a cemetery in Massachusetts near the grave of an officer who he later found out was wounded at New Market Heights. He had collected a good bit of information and was kind enough to share it with us. Doing some additional digging, I was able to find even more.

The 6th United States Colored Infantry (USCI), a unit raised primarily in Pennsylvania and that included three Medal of Honor recipients at New Market Heights, suffered significant losses during the battle. After combing through the compiled military service records for the soldiers of the regiment, my count of their casualties included 46 killed, 21 fatally wounded, five missing in action, and 112 who were wounded but survived. According to John McMurray, the captain of Company D, he went into battle with 32 men and only three answered the roll call after the battle.[1] The regiment’s officer corps was particularly hard hit; 14 of the 18 who went into battle were casualties. The regiment as a whole suffered over 55 percent casualties.

Lt. Eber C. Pratt, 6th United States Colored Infantry (Find A Grave)

Among the 6th’s officer casualties at New Market Heights was Company G’s 2nd Lt. Eber Carpenter Pratt. Lt. Pratt, a native of Southbridge in Worcester County, Massachusetts, began his service in the 34th Massachusetts when he enlisted in July 1862, as a 22-year-old corporal. The 34th was one of the units that manned the Washington defenses during Pratt’s time with the regiment. Pratt’s enlistment with the 34th came to an end when he received a discharge at Harpers Ferry on July 26, 1863, to accept a promotion to 2nd lieutenant and assignment to the 6th USCI. Pratt shared some thoughts about his motivations for transferring to a USCT regiment in letters he wrote often to the Southbridge Journal, his hometown newspaper and former employer. He was highly patriotic in his belief in a perpetual United States, expressed the need to end slavery, and was frustrated by not seeing action in the Washington defenses.

After a period of training at Camp William Penn near Philadelphia, and under the command of Col. John W. Ames, the 6th USCI transferred to Virginia’s York/James River peninsula where they continued training and conducted a series of raids during the winter and spring of 1864. They, along with the 4th, 5th, and 22nd USCI were soon assigned to Col. Samuel Duncan’s Eighteenth Corps brigade and saw their first true combat during the June 15, 1864 assaults at Petersburg.

After spending much of June and July in the ever-expanding trenches at Petersburg, in August the 6th spent some time at Dutch Gap, with a number of men working on Gen. Benjamin F. Butler’s canal project. Dutch Gap was situated upstream on the James River just a few miles from the Deep Bottom Landing pontoon bridge that Butler secured in June.

Just six days before the Battle of New Market Heights, Col. Ames recommended Lt. Pratt for promotion to 1st lieutenant to replace the deceased Myron C. Kingsbury, who was killed by the accidental explosion of a shell at Dutch Gap on September 15. Ames mentioned that Pratt was “worthy of the position and entitled the promotion.” However, before the promotion could be enacted, the 6th USCI received orders on September 27 to report to Deep Bottom Landing.

By the time of the Battle of New Market Heights, Lt. Pratt received an assignment to serve on Col. Samuel Duncan’s brigade staff. In an excerpted letter printed in the Southbridge Journal on October 14, 1864, Pratt explained to his parents some of his battlefield experiences at New Market Heights. Pratt wrote the letter four days after the fight from Chesapeake Hospital at Fort Monroe.

Lt. Pratt was sent to Chesapeake Hospital at Fort Monroe to recover from his New Market Heights wound. (Library of Congress)

In his letter, Lt. Pratt explained that at about 5:45 am on September 29, “I was wounded by a minie ball above my right knee. The ball passed through my leg, shattering the bone.” After receiving the wound, Pratt stated that he “laid on the field for over two hours. . . .”

Between the initial attack by the 4th and 6th USCI, which was repulsed by the entrenched Confederates and when Pratt was wounded, and a follow up assault by the 5th, 36th and 38th USCI, the Confederates came out of their earthworks on to the battlefield and took arms and equipment from the dead and wounded Federals. Pratt was among the plundered. He wrote that he “was robbed of my hat, cap, haversack, woolen and rubber overcoats,” and noted that had he been able to walk he, too, would have been taken, as a prisoner. Instead, not wanting to be burdened with a wounded man, they left him on the field. Later that afternoon, Pratt lost his leg to amputation.

Backing up in the story of the battle, Pratt explained that when the fight began he was on horseback between the forward skirmishers and the main battle line of the 4th and 6th USCI. “I knew what was the matter as soon as I was struck; my leg fractured—useless,” Pratt wrote. Seeing Pratt fall from his horse, Col. Duncan sent someone to help him. Apparently, at least two soldiers reached Pratt, as he noted, “One of the men that stayed by me was captured by the Rebels.” As no officers were reported captured from the brigade, it must have been a Black enlisted man or non-commissioned officer that assisted Pratt and became a prisoner. The other soldier who arrived “went to the rear to get a stretcher. He was also the means of saving my sword and revolver,” Pratt penned.

Lt. Pratt was serving on Col. Samuel Duncan’s brigade staff at the time of his wounding.

The letter ends with Pratt telling his parents, “I do not suffer much; I could suffer more and bear it. My right leg is gone; my hands and other leg are left, and should I not be thankful? My wound is not dangerous and I am well cared for.”

It is more likely that Lt. Pratt suffered terribly and that he was putting on a brave face for his folks in effort to lessen their concerns. He died about two and a half months after writing the missive. Three days before Pratt’s death, he received promotion to 1st lieutenant of Company H.

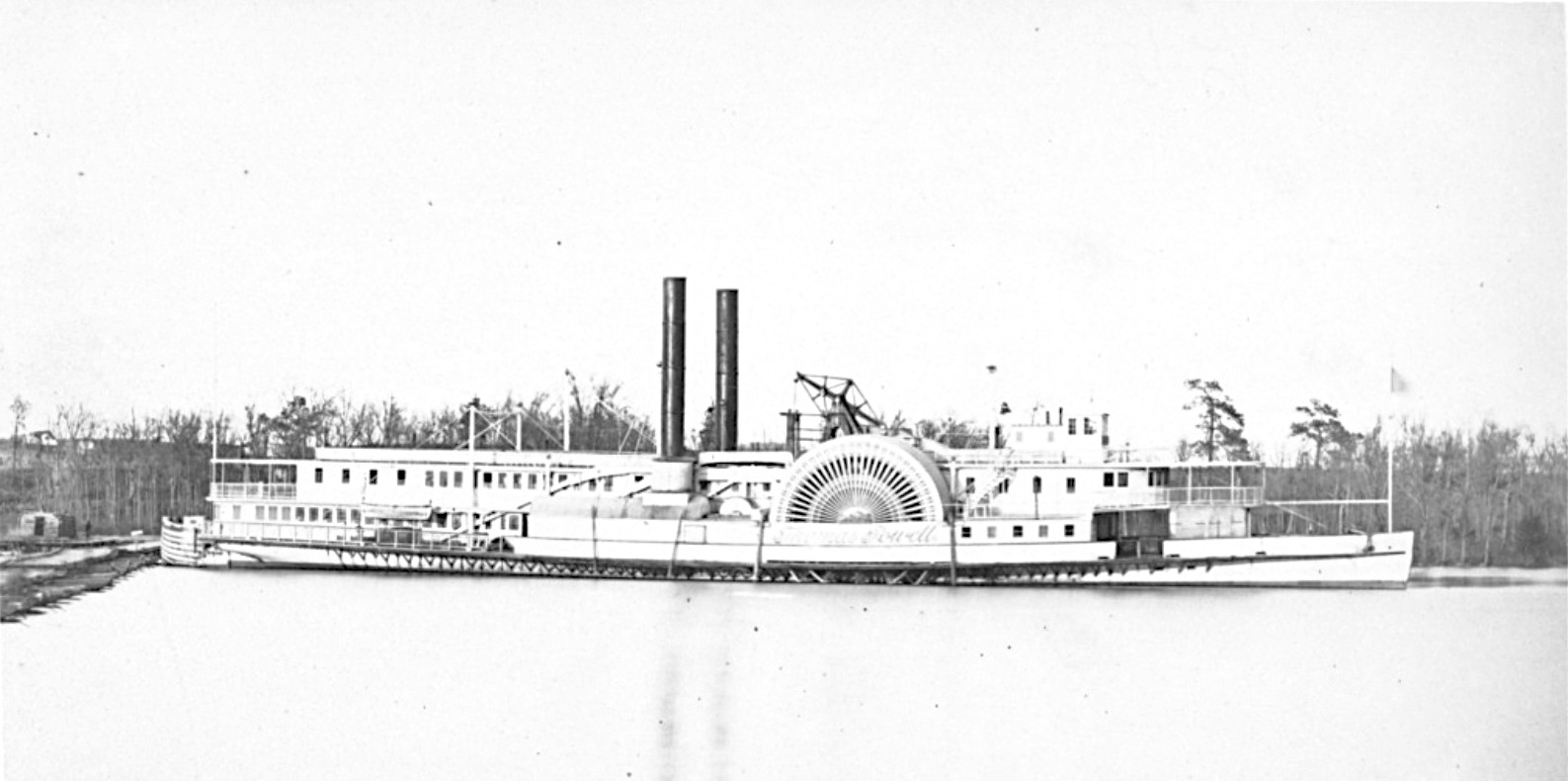

The Federal wounded at New Market Heights were moved from the battlefield to Deep Bottom Landing where they received initial treatment, then, as outlined in Gen. Butler’s plan for the battle, boats were on hand to transport the wounded to formal hospitals at Point of Rocks near Petersburg, Fort Monroe, and Balfour Hospital at Portsmouth, Virginia. Lt. Pratt arrived at Fort Monroe’s Chesapeake Hospital on October 1.

Hospital transports like the Thomas Powell, shown here, carried wounded USCTs to hospitals at Point of Rocks, Fort Monroe, and Portsmouth, Virginia.

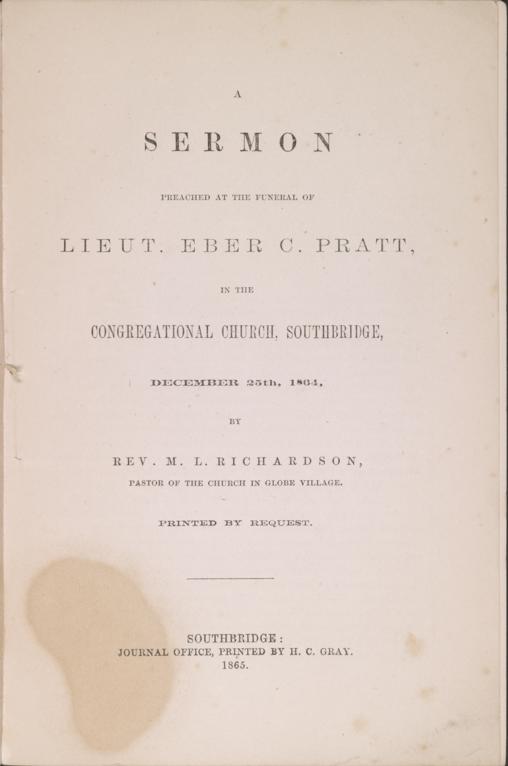

After the return of Pratt’s body to his native Southbridge for interment in Oak Ridge Cemetery, Rev. M. L. Richardson conducted a funeral on Christmas Day, 1864. Rev. Richardson’s full sermon was published in 1865. It covers nine typed pages.

Lt. Pratt’s Grave in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Southbridge, Massachusetts (Jennifer Montigny Riedell, Find A Grave)

It is obvious from Rev. Richardson’s comments that he did his research on Lt. Pratt, probably interviewing family members, Pratt’s wife Clara, as well and reading some of Pratt’s letters home, which he occasionally quotes from, including the letter printed in the Southbridge Journal mentioned above.

After about five pages of language commonly found in funeral eulogies, Rev. Richardson offers some biographical information about Lt. Pratt and a bit of additional information concerining his care following his wounding. For example, Richardson notes that after Pratt’s amputation, “A Major, who had some acquaintance with him, said subsequently, that [Pratt] was the coolest, patientest, calmest man, in such trying circumstances, he ever saw.” A chaplain noted that Pratt “desired to recover and enter the army again,” while a friend mentioned that Pratt said “I have lost a limb, but I am willing to lose it for my country!” Unfortunately, Richardson does not offer much other information about Pratt’s hospital experience, but states, “A deadly disease, which operated to distribute the purulent poison arising from his wound through his system, broke his strength and hopes of life. . . .” A note in Pratt’s widow’s pension application corroborates this account, giving the reason for the lieutenant’s death as pyaemia (blood infection).

Title page for Rev. Richardson’s funeral sermon for Lt. Pratt (Library of Congress)

Rev. Richardson called Pratt “an undisguised detester of slavery and despotism,” and that the young officer was “Eagle-eyed to see the dark deformity of the atrocious evil” of the institution. He also stated that Pratt did not expect to see slavery’s “downfall without some severe sacrifices and shakings.” Quoting from one of Pratt’s letters, Richardson pointed out, “The boom of the rebel cannon which smote the air when Sumter was attacked was the death knell of slavery, rung by the blood-stained hands of its infuriated votaries. The last act of the drama will be the burial of the last relic of barbarism by the constitutional power of the Union it has insulted and sought to overthrow.”

As one might imagine, Richardson included some thoughts on Pratt’s talents, like writing and music, and numerous comments on his Christianity and patriotism.

Expounding on Pratt’s patriotism, Richardson shared a story about Pratt while he was attempting to recover in the hospital from his amputation. The 1864 presidential election results were set to come in that November day and Pratt was restless to hear the final count. Learning that the returns were not yet all in he went to sleep and woke up about midnight and asked again. When informed that almost every state went for Lincoln, Pratt replied, “That is good! I can lie here six months with pleasure now!” Richardson continued, “These words, and the sacrifices he had made for his country’s perpetuity and our good, show how indissolubly was a sacred patriotism incorporated into the very texture of his being. They speak to us all, that we may be anxious to uphold and cherish the liberties which cost so dearly. Let us heed their sad significance, and strive to honor our heritage of blessings by a high Christian manliness and undoubted piety. These alone are our nation’s hope and the hope of the world.”

Eber and Clara did not have children. Clara remarried and became Clara Hardon. She and her husband Charles had a daughter named Rachel Elizabeth. Rachel Elizabeth died at five months old in 1869, and sadly Clara soon followed dying at age 28 from consumption on March 1, 1870.