During the mid-nineteenth century, Oberlin, Ohio, known as a “hotbed of abolitionism,” and even referred to as “the town that started the Civil War,” became a magnet of relocation for both self-emancipated and free people of color seeking a greater sense of liberty, autonomy, and equality. Oberlin College, founded in the early 1830s, and soon thereafter dedicated to providing a co-educational and interracial educational experience, produced a generation of abolitionist-minded Black and White graduates by the eve of the Civil War.

Famous—or infamous, depending on one’s period perspective—for the successful rescue of John Price, a self-emancipated man from Kentucky in 1858, and the adopted home of African American John Brown Harpers Ferry raiders, John Anthony Copeland and Lewis Leary, activist-abolitionism was a way of life for many Oberlin residents by the time of the Civil War.

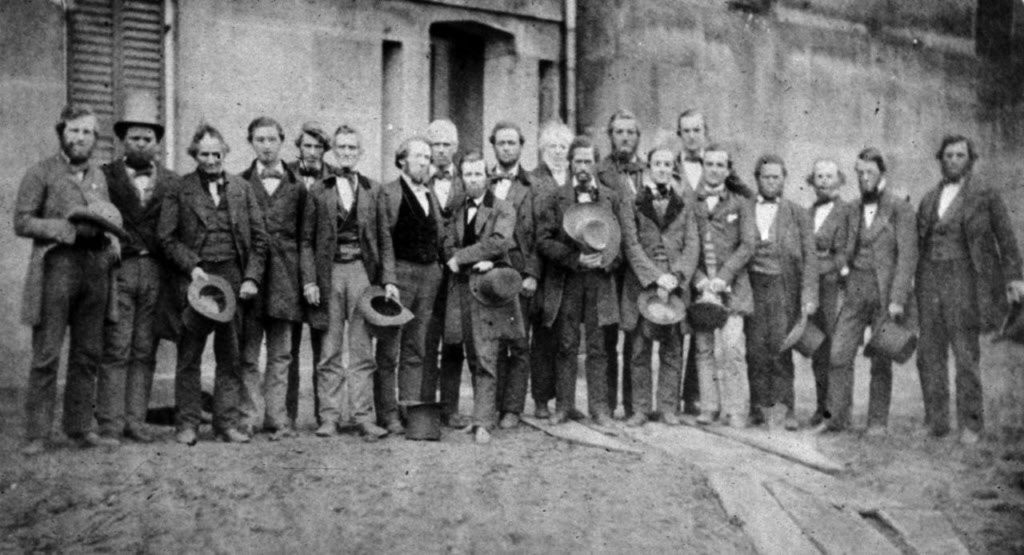

The integrated Oberlin-Wellington Rescuers in 1858. Image in the public domain

As was the case with Copeland and Leary, Henderson Taborn emigrated to Oberlin from North Carolina. And like Copeland and Leary, Taborn was born a free man of color. Despite being free, people of color still existed as basically second-class residents with precious few rights in the slaveholding states. Taborn, and many others, left upper-South states like North Carolina, seeking better immediate opportunities and a more hopeful future for their descendants. For many, Oberlin proved to be their promised land.

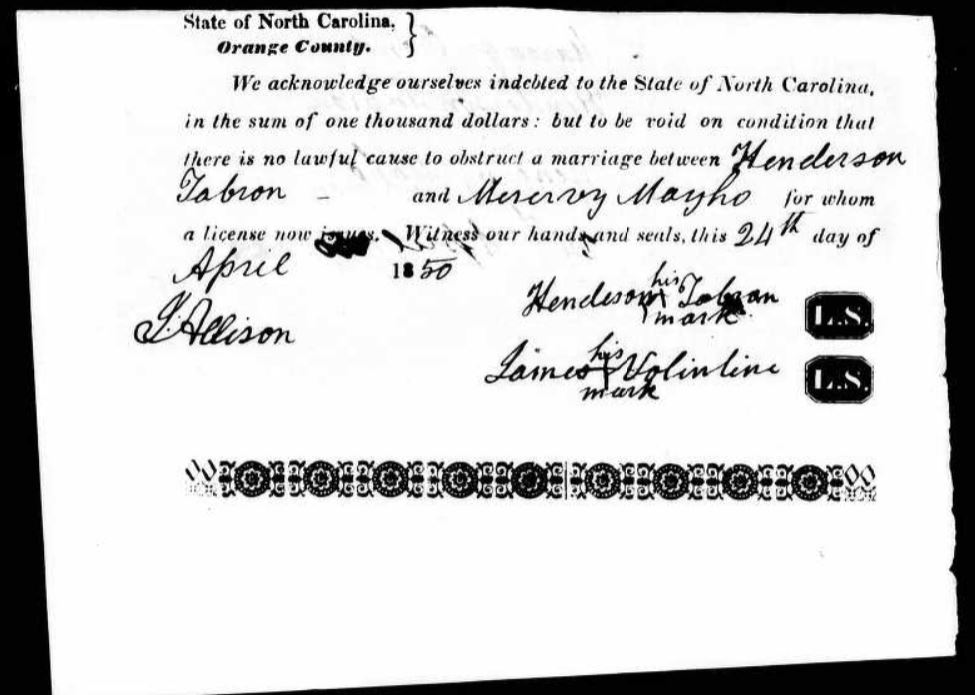

Henderson Taborn began life about 1823 in Orange County, North Carolina. Before relocating to Ohio he lived in the towns of Chapel Hill and Hillsborough where he honed his skills as a cabinet maker. Records show Taborn married Minerva Mayho on April 25, 1850, in Orange County. The couple’s union produced three children in North Carolina: Sally Ann, George, and Henderson, Jr. According to one source, the growing family moved to Oberlin toward the end of 1860 or early in 1861, just as the clouds of civil war began to gather. The Taborns welcomed two more additions to the family circle after moving to Ohio, sons Samuel and Thomas.

Marriage Certificate for Henderson Taborn & Minerva Mayho, 1850. Image courtesy of Ancestry.com

Most of Oberlin’s early war White enlistees viewed the conflict from an emancipationist perspective, in addition to the stated purpose of maintaining the Union. Town men such as Giles Waldo Shurtleff joined regiments such as the 7th Ohio Volunteer Infantry and battled to end slavery’s stain on the United States before emancipation was an officially stated war aim. A number of Oberlin’s Black men jumped at the opportunity to join the 54th Massachusetts Infantry and left for training in the spring of 1863, but Henderson Taborn was not among them.

In the fall of 1863, when the opportunity arose for Ohio to raise its own regiment of African American troops, Henderson Taborn did not enlisted in what became the 5th United States Colored Infantry. At about 40 years of age, and with a wife and five children to provide for, perhaps Taborn thought soldiering was a calling for Oberlin’s younger Black men. Maybe he also understood that African Americans had obtained few benefits from previous military service to the United States. Maybe he was disheartened by the unequal pay Black soldiers received or the lack opportunity for advancement beyond the non-commissioned officer level. By the beginning of 1864, Ohio started recruiting another USCT regiment, the 27th USCI, but again, Taborn was not among its rank and file.

However, on September 1, 1864, Henderson Taborn enlisted in the 5th USCI in Wooster, Ohio. Nothing in his complied military service record indicates that he was drafted or was serving as a substitute for someone else. Perhaps Taborn heard or read about of the performance of fellow Oberlin men who fought in the 5th USCI on June 15, 1864 at Petersburg, or neighbor men who struggled bravely in the 27th USCI at the Battle of the Crater on July 30, 1864. Maybe those reports prompted him to offer his service to do his part to end slavery, show that Black men could be as brave as White men, and to help the United States—now officially dedicated to emancipation—defeat the slaveholding Confederacy. Taborn did not tell us why, so we do not exactly know. All we know is that he enlisted.

Taborn’s enlistment records state he enlisted on September 1, 1864, was 41 years old, five feet eight inches tall, and a cabinet maker by trade. The enlisting officer noted his complexion as “black.” Nothing in Taborn’s records indicate what transportation the army used to get him to the fighting front in Virginia in such a short period. He may have traveled partly by train to Washington D.C., and from there by boat or ship down the Potomac to the Chesapeake Bay and then up the James River to the 5th USCI’s camp.

It is clear that Taborn received little if any significant training for what he would soon face. Travel time from Wooster, Ohio, to the war’s front in central Virginia took a least a week, if not two. Taborn probably had little opportunity to make acquaintance with his comrades, learn to cook his hardtack and salt pork, boil coffee army style, or even get his brogans and new uniform broken in before the 5th USCI received its next combat assignment.

On the morning of September 29, 1864, less than a month after enlisting, Taborn and the 5th formed a second wave of an assault by the Army of the James’ Third Division of the XVIII Corps, against the Confederate earthworks along the New Market Road defended by the famous Texas Brigade. After witnessing the terrific casualty rate the first attack wave (4th and 6th USCI) encountered, the 5th USCI received orders to lead another attack, followed in column by the 36th and 38th USCIs. The 5th USCI took advantage of holes in the two lines of abatis that the first attack created, but the firepower of the Confederates was initially too much to bear and the attack stalled. Suffering terrific casualties among the officers and enlisted men, many of the non-commissioned officers took over their companies and got their momentum going again, surging forward, and with the weight of the 36th and 38th USCIs, drove the rebel defenders out of their entrenched position.

Among those in the 5th USCI recognized for their feats of heroism were first sergeants Robert Pinn, Milton Holland, James Bronson, and Powhatan Beaty, who all received the Medal of Honor for their courage under fire. Oberlin’s Lt. Col. Giles Waldo Shurtleff, now commanding the 5th USCI and wounded twice in the attack, remembered during the battle that some of the Confederates yelled derisively to the USCTs, “’Come on you smoked Yankees, we want your guns.’” While the second attack bogged down, Shurtleff recalled, “the most murderous fire that I witnessed during the war, opened upon us.” Already wounded once, Shurtleff gave the soldiers the command to “’Forward double quick’ and they went over the abbatis with a shout, and carried the works, the enemy retreating as soon as the obstructions were passed.”

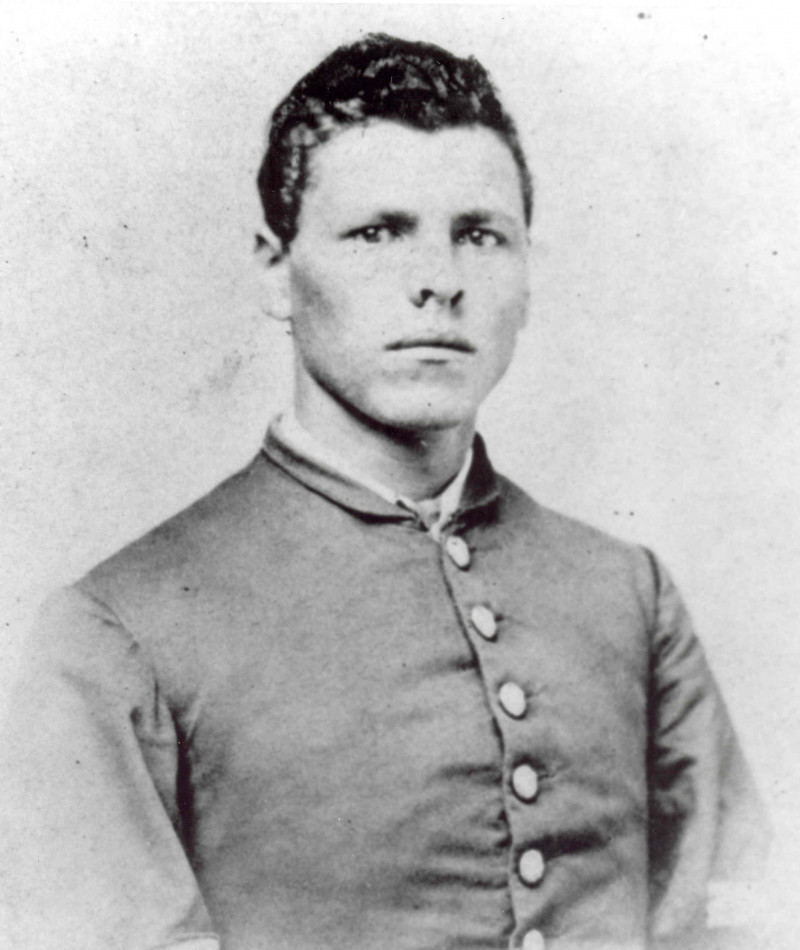

First Sgt. Milton Holland was one of four 5th USCI soldiers who received the Medal of Honor for courageous actions at the Battle of New Market Heights

Scattered on the ground before the enemy earthworks, the casualties of the 5th USCI—who lost about half their men—included newly minted soldier Pvt. Henderson Taborn. It is unknown at what point in the attack life left his body, but Lt. Col. Shurtleff, and Lt. James Marsh, who was quartermaster for the 5th USCI, provided affidavits for the pension claim of Taborn’s wife, Minerva, that they heard about Taborn’s death on the battlefield from two of Taborn’s comrades captured during the attack and who were later paroled and eventually returned to the regiment. These two unnamed enlisted men saw Taborn lying dead on the battlefield.

Pvt. Henderson Taborn likely received a burial on the field of battle. Whether Taborn was later removed to a National Cemetery as an unidentified soldier or missed during the interment process, is unknown. Although he was a United States Colored Troops soldier for less than a month that does not in any way detract from the sacrifice he willingly made with his life to his country and for the advancement of human rights. We remember Pvt. Taborn and praise his courage and determination despite the many dangers surrounding him during the Battle of New Market Heights. May he and his comrades never be forgotten!