On August 4, 1864, Capt. Henry F. Young, 7th Wisconsin Infantry, wrote home to his wife sharing his sentiments about Black troops in the wake of the Battle of the Crater. “My opinion is that negro troops with white officers will not do . . . ,” he wrote. In his view—one shared by many White Federal soldiers, as well as their Confederate foes—it was only necessary for the enemy to shoot the White officers to throw the Black enlisted men and non-commissioned officers into a panic.

At the Battle of the Crater, according to Capt. Young, “the enemy shot nearly all their white officers knowing that the negroes would be worth nothing without their officers and so it proved as soon as their officers were not there to lead them the negroes were no better than a lot of scared sheep.” Two days later, Young wrote to his father-in-law restating what he informed his wife and pinning blame for losing the battle on the performance of the United States Colored Troops. There were many reasons for failure in the July 30, 1864, battle at Petersburg, but the Black troops was not one of them. Prejudice clouded the thinking of many White soldiers on both sides.

Despite earlier evidence to the contrary at Milliken’s Bend, Battery Wagner, Port Hudson, and closer by at Wilson’s Wharf on May 24, and at Petersburg on June 15, White soldiers continued to express skepticism about the ability of Black men in combat. It took additional examples, like the Battle of New Market Heights, to start to change some minds. Sadly, some never changed. At the Battle of New Market Heights, Black non-commissioned officers, and even enlisted men, stepped into leadership roles and gained victory, in many cases after numerous White officers fell killed and wounded. Fourteen Black men received the Medal of Honor at New Market Heights as proof. Many other men, like 1st Sgt. William Henry Hazzard, Co. K, 6th United States Colored Infantry, fell while fulfilling their duty.

According to information in his compiled military service record, Hazard was born in New Castle County, Delaware, however, other sources state he was born in Pennsylvania. Information from several sources indicate Hazzard was born about 1840. Census records show that Hazzard’s father, Solomon, moved to Thornbury Township in Delaware County, Pennsylvania by 1840. What is not so clear is when William Henry Hazard and his sibling(s) came to Pennsylvania or if they were born soon after Solomon Hazzard arrived. The 1840 census only indicates two adult individuals in Solomon Hazard’s household. Regardless, by the 1850 census, the Solomon Hazzard family of four, consisting of wife Mary and sons William and Solomon, lived in Thornbury Township. Solomon Hazzard’s occupation is listed as laborer, and he owned $650 in real estate. The census shows that Solomon and Mary were both born in Delaware, and sons, William and Solomon, Jr., were born in Pennsylvania.

A decade later the family was still together, except Solomon, whose age in 1850 was 74, and had apparently died. Mary, 70-years-old in 1860, is listed as a widow with only $20 in personal property. William’s age is 20 and Solomon, Jr. is 17. William and Solomon both were both laborers.

Pension file records for William Henry Hazzard state that he married Louisa Gooden on December 8, 1859, in the Methodist Episcopal Church in West Chester, Pennsylvania, officiated by Pastor J. M. McCarter. One wonders why Louisa is not included in the 1860 Hazzard family household in Pennsylvania since she and William married about nine months before the census taker made his count. The pension records also state that William Henry and Louisa’s union produced a son named Isaac, who was born on September 20, 1860, in New Castle County, Delaware. Louisa appears in the 1860 census in her parents’, Isaac and Margaret Gooden’s, household in New Castle County, as a 19-year-old. Louisa would have been pregnant with baby Isaac at the time of the census.

On March 9, 1863, William Henry’s Hazzard’s younger brother, Solomon, enlisted as a private in Company B of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry in Readville, Massachusetts. His service records state that he received a wound at that regiment’s July 18, 1863, assault on Battery Wagner, South Carolina, the battle depicted in the motion picture Glory.

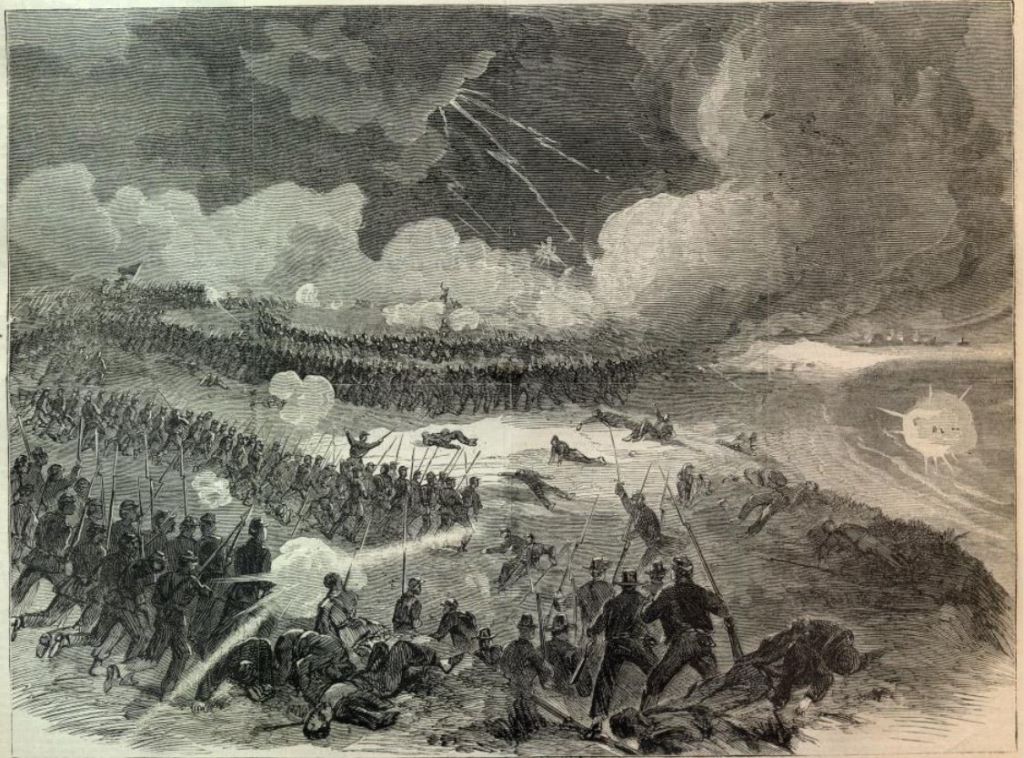

William Henry Hazzard’s brother, Solomon, served in the 54th

Massachusetts Inf., and was wounded at Battery Wagner. From Harper’s Weekly.

About the same time Solomon was fighting in South Carolina, William Henry Hazzard’s was drafted and he enlisted in Company K, 6th USCI on August 12, 1863, in Smyrna, Delaware. Perhaps William had moved to Delaware to be with Louisa and toddler son Isaac before or early in the war. William’s enlistment records describe him as 25-years-old, five-foot ten-inches tall, and having a “Black” complexion. He officially mustered into service on September 12 and received the rank of first sergeant four days later.

First Sergeant Hazzard endured the heavy marching that the regiment experienced on the York River/James River peninsula in the spring of 1864 while his regiment sharpened their soldier skills. However, the unit transferred to the Petersburg front in early June. It appears he survived the regiment’s initial combat at Baylor’s Farm and along the Dimmock Line on June 15 without injury. It is unclear if he was among the soldiers who labored on the Dutch Gap Canal in the summer of 1864, but it is likely he did while the regiment was stationed there.

Ordered to travel the short distance by boat to Deep Bottom Landing, Hazzard and the 6th USCI arrived at their destination on the night of September 28, 1864. Given little time to rest and eat their rations, the regiment was up and moving to get into position well before daybreak. Ordered to carry only their blanket roll, three days of rations, and 60 cartridges per man, they lined up near the Buffin House, just north of Kingsland Road. With their brigade mates, the 4th USCI in position in their front and offset a little to the right, two companies of the 6th USCI received the unenviable job as skirmishers. Company A, and Hazzard’s Company K, were ordered to handle the assignment.

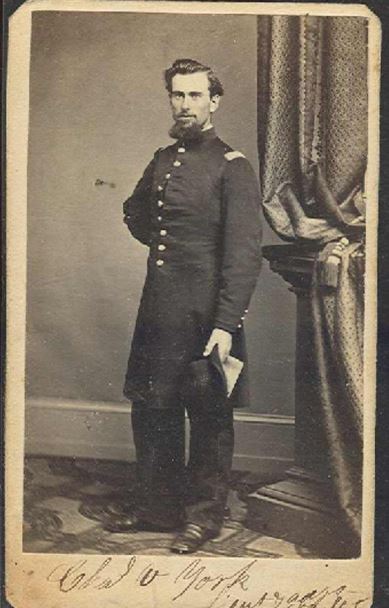

When White officers like Capt. Charles V. York (pictured above) fell in great numbers

at New Market Heights, Black soldiers continued to perform well under fire.

In skirmish formation, Hazzards’s non-commissioned officer rank was of great importance due to the dispersed style of fighting and the challenge of commanding and controlling the enlisted men while under fire. During the skirmish fighting, Capt. Robert Beath of Company A received a leg wound severe enough to cause him to leave the field and undergo an amputation. Also wounded in Company A were Privates James Cooper, David H. Irons, and John Wright. Hazzard’s Company K fared much worse. William Lewis and Albert Waters were killed. Wounded were Charles Berry, David Coston, Isaac Gales, Joseph Gales, Sgt. Charles Garner, Corp. Alexander Henry, Isaac Hubbardton, Isaac Lee, James Manlon, Edward Mills, Isaac Purnell, Corp. Edward Raner, Isaac Robinson, John Short, William Snowden, and Corp. William Williams. Those fatally wounded were Perry Hamilton, and 1st Sgt. William Henry Hazzard. Hazzard received a gunshot wound to his left leg.

Dispelling the myth that Black men could not endure combat,

two of Hazzard’s African American 6th USCI comrades

(Sgt. Maj. Thomas Hawkins & 1st Sgt. Alexander Kelly) received the Medal of Honor

for heroism at the Battle of New Market Heights. Image courtesy of Don Troiani.

Removed from the field, Hazzard underwent an amputation and then traveled by a hospital transport ship to the Point of Rocks hospital at Bermuda Hundred near Petersburg. Among the papers in Hazzard’s minor son’s pension file is an affidavit made in June 1867 by Hazzard’s company commander, Capt. Girard P. Riley, who was then living in Clermont County, Ohio. In it Riley states that Hazzard was wounded in the leg while on the skirmish line at New Market Heights and that he was “carried back to the rear, and his leg amputated, from thence removed to Base Hospital at the Point of Rocks.” Details do not exist about the complications that developed from Hazzard’s amputation and sadly resulted in his death on December 30, 1864, but it was probably due to an infection.

| Point of Rock hospital complex. Courtesy of the Library of Congress. |

Unfortunately, Louisa Gooden Hazzard died on January 8, 1865, only surviving her soldier husband by about a week. Little information in the records reveal the facts of her death, but an affidavit from Louisa’s parents, Isaac and Margaret Gooden, state that she died at Mill Creek Hundred in New Castle County, Delaware, and “that they knew of her last sickness and attended her in the same, That her death occurred in their house and they attended her funeral.” One wonders if she had even received the news of her husband’s death before her own.

Isaac T. Hazzard received the guardianship of Eber Sharp, a White farmer living in Chester County, Pennsylvania. The records do not detail why Isaac and Margaret Gooden did not become the legal guardians of their grandson. However, a review of the Eber Sharp household in the 1870 census shows his next door neighbor as being Lucy Hazzard, a 70-year-old housekeeper and perhaps Isaac’s great aunt. Also in her house are Joseph Hazzard (26), and Isaac T. Hazzard (12), who is the only person in the house with personal property, and it valued at $200. This money may be his pension-funded savings.

Perhaps Isaac Hazzard used some of his money to pay for an education, as he appears as a student in the “Preparatory Department” of the Lincoln University (a historically Black school near Oxford, Pennsylvania) catalog for 1878. Another record appears indicating that Isaac married a Sarah Hillyard in 1888, and an 1890 Philadelphia city directory lists Isaac as a clerk. The following year’s city directory lists Sarah Hazzard “wid[ow] Isaac” as living at 1342 Rodman Street. Additional research did not locate the cause of Isaac Hazzard’s death.

First Sgt. Hazzard originally received burial in the Point of Rocks hospital cemetery. After the Civil War the soldiers buried at Point of Rocks received reinterment in the City Point National Cemetery at present-day Hopewell, Virginia. Unfortunately, Hazzard is not among those identified. He probably rests in peace in one of the cemetery’s 1,400 unknown graves.

We salute 1st Sgt. William Henry Hazzard and his willingness to serve the United States in its time of need. During his life he was an agent of liberty for the enslaved and a beacon of future citizenship for his son and millions of others seeking equality and a more perfect Union. We remember!