Although our soldier-focused articles are often titled “Dying Far From Home,” this one may be somewhat mislabeled. Sgt. Richard Servant’s compiled military service records indicates that he was born at Fort Monroe, Virginia. He died on November 6, 1864, at Balfour Hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia, from a wound or wounds received at the Battle of New Market Heights. If indeed, Sgt. Servant was born at Fort Monroe, he died just a short boat ride away from the scene of his nativity. One wonders if he pondered such thoughts as he lay in his hospital bed attempting to recover.

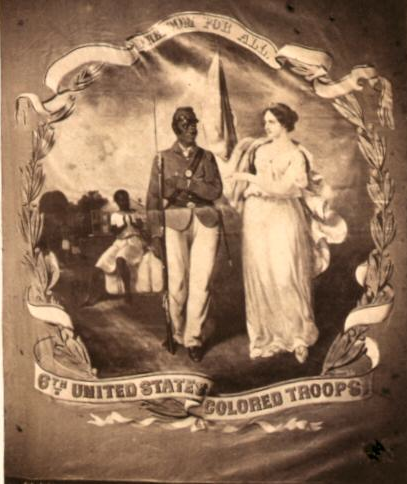

Richard Servant was apparently born around 1839. As stated above, his place of birth is noted as Fort Monroe. Somehow, someway, Servant ended up in Philadelphia where he enlisted in Company D, 6thUnited States Colored Infantry (USCI) on August 10, 1863. A search through the 1860 census did not locate Servant, so it is unclear whether he was a recent arrival to the “City of Brotherly Love,” or if he had been there for quite some time. It is also unknown whether he was enslaved or a free man of color before enlisting.

The 24-year old new recruit and former “laborer” stood five feet, eight inches tall, and was described as having a “black” complexion. He must have impressed his white officers at Camp William Penn, because within three weeks of his enlistment he received appointment as a sergeant in the company.

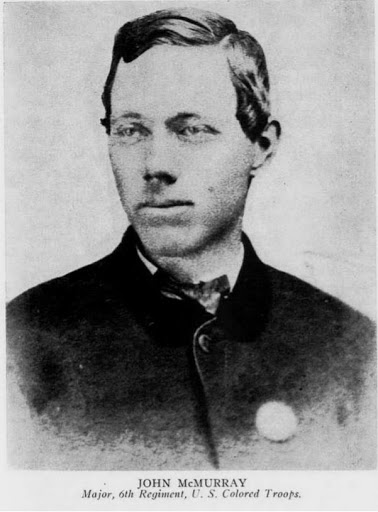

Capt. John McMurray led Company D. McMurray left a memoir, written in 1916, titled Recollections of a Colored Troop, which gives keen insight into the terrible damage inflicted upon his company and how they responded with amazing acts of courage at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864.

Following the 4th USCI, who led the attack, the 6th USCI immediately took heavy casualties when they reached lines of abatis, which accomplished its intended work of slowing the assault. However, as McMurray recalled, they “pressed on toward the enemy’s line, picking our way through the slashing as best we could. It was slow work and every step in our advance exposed us to the murderous fire of the enemy.”

At one point in the attack McMurray remembered: “When about half way through the slashing I came to a large oak tree that had been felled. At the same time three or four members of our color guard came to the same spot. We were close by the stump of the tree, and the way forward was through an opening between the trunk of the tree and its stump, less than three feet wide. Involuntarily, almost, I paused to let the colors go ahead of me. I followed close after, and just when the last one of the men, carrying one of our flags—we had three—was right in the opening between the stump and the tree trunk, he was shot through the breast, and fell back against me, almost knocking me over. The loss of his life there absolutely saved mine.”

The toll on the 6th USCI was high, and particularly so for Company D. Falling back, “As we soon as we passed over the hill a sufficient distance to be protected from the rebel shells, we began to reform the regiment, as the men were all mixed up. As I could find but three of my company it did not take me very long to form them in line, and I turned to assist in getting the men of other companies in line,” said McMurray.

It is unknown when during the attack Sgt. Servant received his wound or wounds. And his service records do not specify where on his body they struck. Removed from the field and transported by hospital steamer, he ended up receiving care at Balfour Hospital in Portsmouth. He survived for what were likely five excruciating weeks before he finally succumbed.

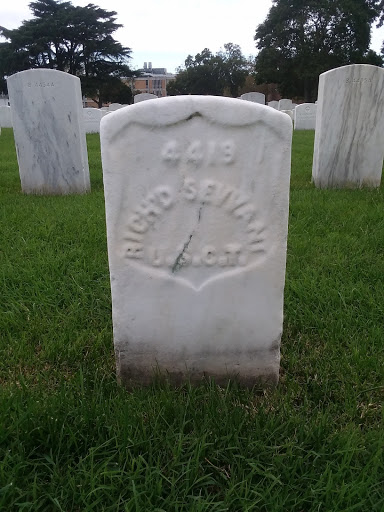

Today, Sgt. Richard Servant rests in grave number 4419 in Hampton National Cemetery with scores of USCT comrades, only a couple of miles away from where he entered life. All honor to you Sgt. Servant for your service and sacrifice.