In my ongoing efforts to recognize the service and sacrifice of the soldiers who fought and died in the United States Colored Troops, I am continually finding so many men interred in my local national cemeteries. Depending on surviving and available primary source documents, sometimes significant backstories can be told about these men, unfortunately, other times, not so much. Regardless, it is still well worth the time and effort to bring at least a measure of acknowledgement to them for their willingness to lay their lives on the line for the ideals of the United States of America.

Pvt. Richard Varney was a mere 21 years old when he enlisted in Company K, 4th United States Colored Infantry on September 2, 1863, in Baltimore. Varney was born enslaved in Talbot County, Maryland. His occupation is listed in his service records as “farmer.” One wonders what occupation Varney might have pursued had he not been enslaved. No information is provided on Varney’s owner. Unlike many Maryland enslaved who served in USCT regiments, no claim for compensation accompanies Varney’s service records. Did he flee slavery to enlist?

As is the case with most soldiers, we are able to draw rough mind’s-eye picture of Varney from his enlistment description. He was of common height for soldiers, standing five feet, five inches. His noted complexion was “griff,” a hue somewhere between black and mulatto. Varney’s eyes were reported as “black” and his hair “curly.”

Not all soldiers rose in rank during their Civil War military careers. In fact, the vast majority did not. Varney entered service as a private and closed out as a private. Not receiving a promotion does not mean that a man was any less of a soldier. The measure of soldier is found in whether he did his duty or not. Pvt. Varney did his duty.

During his enlistment, the only thing that took Varney away from his company and regiment was an undisclosed illness in late June of 1864. It was severe enough to require a hospital stay of undetermined duration. However, he returned to duty two months later, detailed to work on the Dutch Gap Canal. This massive earth removal project was an attempt to bypass some of the Confederate shore defenses along the twisting James River. It was very unpleasant work in dangerous conditions, with the workers often enduring Confederate artillery fire.

Dutch Gap Canal

On September 28, 1864, Pvt. Varney along with his officers and comrades from the 4th USCI left Jones Landing via gunboat transport and soon disembarked at Deep Bottom. The 4th made camp that evening and got a little sleep. According to Sgt. Maj. Christian Fleetwood, some men made coffee before forming up to make the assault on the Confederate earthwork lines along New Market Heights Road.

The 4th led the attack. Before stepping off, the soldiers received instructions to leave their knapsacks, to take only a blanket roll, haversack, and canteen in addition to their rifle musket and accouterments. In addition, the men were to load their rifles, but not cap them, and to affix their bayonets. Right behind and just offset to the left of the 4th, the 6th USCI followed.

It is unknown at what point in the assault, whether it was before reaching the Confederate abatis obstacles or among it, but Pvt. Varney received wounds to the head, right arm, and his right side. Unlike many of his comrades, Varney left the New Market Heights battlefield still clinging to life. Transported to the XVIII Corps base hospital at Point of Rocks, on the Appomattox River near City Point. Efforts to treat Pvt. Varney’s wounds ultimately proved unsuccessful. He passed away on October 8.

Point of Rocks Hospital Complex

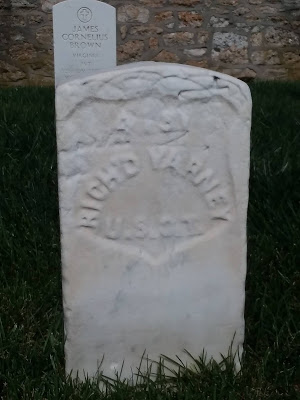

Originally buried at the Point of Rocks soldier’s cemetery, Pvt. Varney was later moved to the City Point National Cemetery where today he rests in peace in grave number 4131. Pvt. Varney, you are remembered!

Period images courtesy Library of Congress.