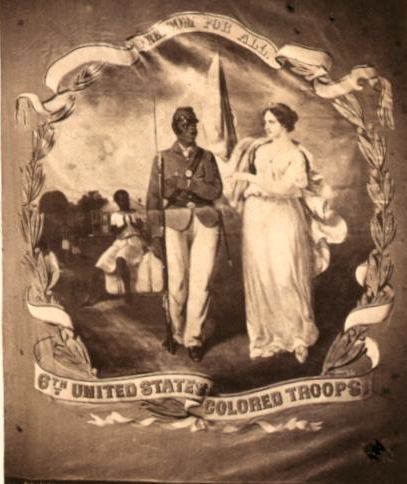

The 6th United States Colored Infantry (USCI) recruited its soldiers largely from the New Jersey, Delaware, and southeastern Pennsylvania area. Organized and mustered in at Camp William Penn near Philadelphia in the summer and fall of 1863, the regiment moved to Virginia for duty that fall.

Not all new recruits were volunteers. Some men came to the ranks by way of the draft. Recent historical scholarship explains that many free African Americans took pause before enlisting or showed little interest in signing up when finally allowed to serve the United States army. Much of the vacillation came from the difficult lessons learned from black service in past conflicts. Participation in the armed forces during the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812 brought few political, social, or economic gains to men of color. Early on, there was not much evidence the Civil War would be different from previous wars in terms of rewards and fulfilling the latent promises of the Declaration of Independence.

We do not know why Perry Hamilton ended up being drafted rather than volunteering. Perhaps he would have enlisted if had he not been drafted first. Perhaps he had his eyes on an opportunity that he felt offered a brighter future. Maybe he was supporting family members financially who could not do without his earnings. Regardless, he fulfilled his duty by enlisting in Company K, 6th USCI on August 13, 1863, at Smyrna, Delaware.

Hamilton’s Compiled Military Service Record provides a brief physical description of the newly minted soldier. The 21 year-old young man measured five feet ten inches tall and possessed a “light” complexion. In the 1860 census, Hamilton appears described as a “mulatto,” residing in the household of Abram and Matilda Brinkly in New Castle, Delaware, which is located just south of Wilmington. There are a number of other individuals in the household, so his may have been an extended family home. His occupation, “laborer,” was by far that which was listed most often by his regimental comrades.

Hamilton, like countless Civil War soldiers, experienced a period of illness during his service that required medical attention. He missed a significant amount of time in the spring of 1864 while in the hospital at Fort Monroe for treatment. His unspecified illness may have prevented him from experiencing the 6th USCI’s first taste of combat on June 15, 1864, at Baylor’s Farm that morning and the assaults on the Dimmock Line at Petersburg that evening. However, apparently after recovering, Hamilton spent time working on the Dutch Gap canal project.

Back in the ranks of the 6th USCI, Hamilton participated in the assault on the Confederate line at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864. Company D’s Capt. John McMurray remembered the thoughts of the soldiers as they anxiously awaited the charge. “I know there was a big lot of thinking done by us while we stood there. We knew there was a strong line of Confederates behind the rifle pits, across the slashing from us. We knew that as soon as we would move forward they would open fine on us. We knew the order to move forward would soon be given. But beyond that, what? Would it be death or wounds, or capture? Would it be victory or defeat?,” he recollected.

Image of the 6th USCI flag courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Company A, and Hamilton’s Company K, served as skirmishers, out ahead of the initial assaulting regiments. Skirmishers, fighting in dispersed formation, probed forward and engaged the pickets of the defenders. It was likely in the role of skirmisher that Pvt. Hamilton received a grievous wound. Right behind the skirmishers, Col. Samuel Duncan’s brigade, composed of the 6th attacking right behind the 4th USCI, tried to make their way though the slashings of abatis. The 4th and the 6th took heavy casualties. According to one count, the 6th lost 42 killed, 161 wounded, and seven missing out of the 367 men and officers who entered the battle.

Evacuated from the battlefield due to a gunshot wound in the back that injured his spine, Hamilton received transportation by boat to Fort Monroe, where he had previously received treatment for a sickness. He must have experienced excruciating pain due to the nature of his wound. Unlike a wound received to a bodily extremity that may receive amputation in effort to mitigate infection and prevent the patient’s death, a wound to the body’s core or head often limited a surgeon’s ability to help. Hamilton suffered for 11 days before death released him from his pain on October 10, 1864. An inventory of possessions showed that Hamilton owned no personal effects.

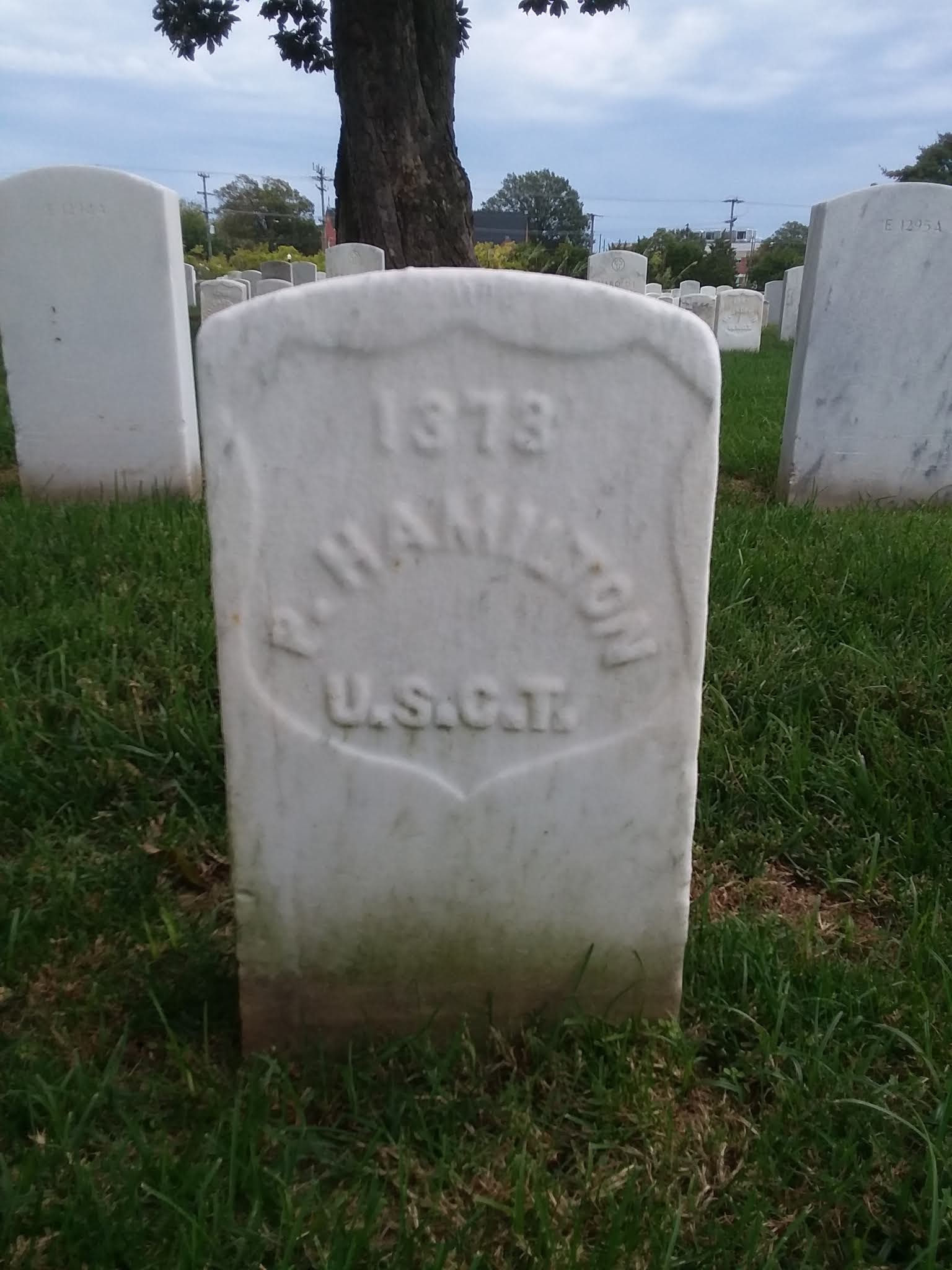

Having faithfully performed his duty, Pvt. Perry Hamilton rests only a few short rows from a shady tree in grave number 1373, and surrounded by fellow soldiers who gave their lives for a “more perfect Union,” in Hampton National Cemetery.