When the Civil War began in 1861, many men enlisted under what historians term rage militaire, or “passion for arms.” During the spring of 1861, both belligerents worked themselves into a fevered pitch. Depending on their side’s perspective, citizens enlisted in mass over the enemy’s blatant attempt to break up the Union, or for having the gall to bring an army into a fellow seceded state. Many of the newly minted soldiers thought the conflict would be a short affair. When neither side seemed interested in throwing in the towel, enlistments slacked, and rage militaire receded.

Men who enlisted after 1861 did so from a multitude of motivations. Some finally came of age, some sought the pay, some took advantage of the bounties, while others were drafted. When African American men finally received the call to arms, their reasons for enlisting, or delaying enlistment, varied, too. Enslaved men often had to make it into Union lines to enlist. In many locations that took time to happen. Some free men of color from the Northern states disenchanted from the lack of benefits gained by their ancestor’s service in previous conflicts, delayed their enlistment waiting for better guarantees before risking their lives for a nation that did not yet recognize them as citizens. Black men in the slaveholding Border States ran into numerous obstacles including physical persecution and threats of selling away family members.

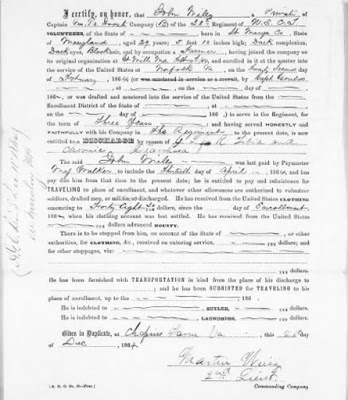

We do not know what motivated John Miles to enlist in Company B of the 38th United States Colored Infantry, or why he waited until February 14, 1864 to join up. Perhaps he was enslaved and his enslaver prohibited his enlistment. Perhaps he was unsure what army life entailed and took time to gather information. Maybe he heard about the many trials faced by other black soldiers who enlisted earlier from his county. Regardless, he officially became a member of the regiment, at Great Mills in Maryland’s St. Mary’s County.

Joining Company B of the 38th the same day was another Miles, George. Both John and George were age 29, both measured at 5 feet 10 inches tall, both apparently had dark complexions, and both were from St. Mary’s County. Were John and George twins?

About a week after enlisting, John and George Miles traveled to Norfolk, Virginia, where they officially mustered in to the United States army and began their training. Initially serving in southeastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina, the 38th soon reported to the scene of war at Petersburg. Both John and George’s service records show them as present for duty through the spring and summer of 1864. However, George received some detached assignments including recruiting, headquarters, and regimental quartermaster department duties. It is unknown if George’s detached duties kept him from participating in the Battle of New Market Heights. If so, John was not as fortunate.

At New Market Heights, on September 29, 1864, the 38th USCI followed the 5th and 36th in the second assault that morning upon the Confederate earthworks. The Rebel obstinacy and USCT determination is shown in the fact that although the 38th was the last regiment in the attack, two of the three men in the regiment who received the Medal of Honor are noted as being among the first to enter the enemy’s works.

Pvt. John Miles fell in the battle, his right tibia (shinbone) shattered by a Confederate bullet. Removed from the battlefield and transported to Deep Bottom landing, John went aboard one of the handful of hospital steamers and headed down the James River to the Fort Monroe hospital complex. Pvt. Miles likely endured an amputation either at the field hospital or at Fort Monroe. Sadly, unable to recover from his painful wound, he died on October 11, 1864. A contributing factor to his death may be a weakened body, as he was also apparently suffering from chronic diarrhea. Today, Pvt. Miles rests in peace in grave number 367 in Hampton National Cemetery.

Pvt. George Miles continued serving in the 38th through the end of the war and endured duty on the Texas/Mexico border, finally mustering out in January 1867. If George and John Miles were indeed twins, George’s painful loss surely continued long after his army service ended.