At this time of the year, I can not help but think how hollow the part of the Declaration of Independence that reads “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal . . .” must have rang to not only enslaved people, but also free people of color in the Civil War era. Making that ideal statement a reality is a primary reason that many African American men put their lives on the line by enlisting and fighting in United States Colored Troops regiments during the Civil War.

One of those men was Henry Winslow. He was an atypical USCT soldier in several ways. First, he was a free man of color. The majority of black soldiers were enslaved just before their enlistments. Second, he was quite a bit older than the typical fighting man. Winslow was 43 when he signed up in 1863. Most men were in their late teens and early twenties. Third, he was six feet tall, which was about four or five inches taller than the average Civil War soldier.

Winslow’s service records give us some excellent information to help fill out his life story a little. But, since he was a free man well before the Civil War, he also appears in earlier census reports. The 1850 census indicates that he lived in Madison County, Ohio, which is just west of Columbus. He shows there as 35 years old, and born in North Carolina. He lived with his wife Susan (21), daughter Sarah Jane (4), and son Richard (2). Also in the Winslow home are: William Jenkins (5), Martha J. Oliver (5), and Frances Lorain (2). Oliver and Lorain are both noted as “pauper.” Although Winslow is not listed owning any real estate, he is listed as owning $40 worth of livestock (including 1 horse) in the agricultural census of 1850.

In the 1860 census, Winslow is listed as a 40-year old farm laborer, and still in Madison County, Ohio. The Winslow family now included: wife Susan (31), and their children: Sarah J. (14), Richard (11), Isiah (9), John (7), and George (5). Susan and the rest of the family were all born in Ohio. Henry apparently owned no real estate or personal property in 1860. Apparently, Susan could not read or write. For some reason two other Winslows, Mary (3) and David (1), along with two other black children: William Dents (7) and Leroy Dents (2) are listed in the household of next door neighbor, John O’Brien and his family. This is probably a census taker error, as the Winslow and Dent children are at the top of the page following the rest of the Winslow family, yet are numbered within the O’Brien family. The Winslows likely served as a type of foster family in 1850 for Martha Oliver and Frances Lorain, and in 1860 to the Dents children.

One wonders if Henry Winslow had a difficult time leaving his rather large family when he enlisted in Company H, 5th United States Colored Infantry on July 7, 1863, in London, Ohio. His service records give us some more information about his place of birth, listing Pasquotank County, North Carolina, albeit with a butchered spelling. Winslow officially mustered into service at Camp Delaware, Ohio, on July 23, 1863. He appears to have been a faithful and healthy soldier, as he is listed as present for duty on every two-month muster card.

Pvt. Henry Winslow’s September/October 1864 card includes sad news: “Died Oct. 2, ’64.” The next card gives a bit more information: “Died from wounds received in action.” Continuing to page through Winslow’s records, the last paper in the group tells clearly what one might suspect for a soldier who died from wounds in action at that time. That page reports, “died at Point of Rocks [Hospital], Va. Oct. 2, ’64 of wounds received at New Market Heights, Va. Sept. 29, ’64.” No details are provided on what type of wounds Winslow suffered.

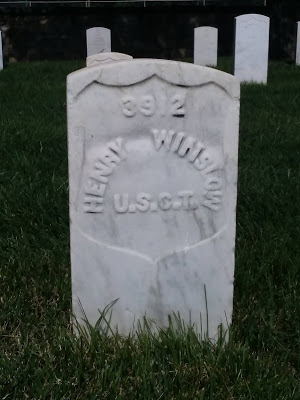

Winslow was likely originally buried at the Point of Rocks soldier’s cemetery. However, later, his remains were moved to the City Point National Cemetery where today he rests in grave number 3912.

On the eve of Independence Day 2020, we salute you Pvt. Winslow for your service, and for sacrificing your life to abolish slavery, stake a claim for the right to be equal to every other American, and preserve the Union, so it may one day be “more perfect.”

Grave marker photograph by Tim Talbott