Drafted! Imagine getting word that the government demanded your service in its military. Since the Civil War millions of Americans have received that call, and thankfully, answered it. However, conscription, a new practice at that time, operated differently then. First, not all eighteen year old males had to register for the draft as our selective service requires today. If congressional districts were unable to meet soldier quotas through recruiting efforts, a draft involving an age range of men potentially brought more soldiers into the ranks. Second, at least initially, drafted men who were wealthy enough could pay a fee to get an exemption, or purchase a substitute to serve in their place. Obviously, those individuals not as economically advantaged had fewer options.

Among the men conscripted from the Third Ward of Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, in the summer of 1863 was James A. Kane, a free man of color. Kane, a native of Allegheny County, worked as a laborer in the decade before the Civil War erupted. In 1850, the 19-year old lived in a full Ross Township household of 11 people, including his 20-year old sister, Sarah. A decade later 28-year old John lived as a boarder in Allegheny City, worked as a “River man,” and claimed no real estate or personal property of value. The head of the household in which John lived, Alexander Sigler, also African American, claimed only $25.00 in personal property. Kane was apparently in no financial position to avoid the draft.

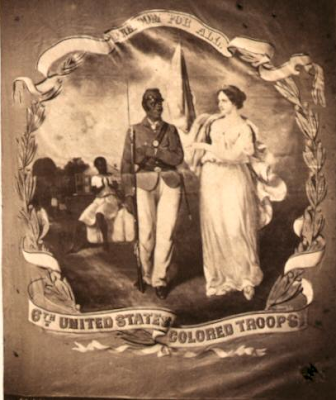

Regardless of whether James Kane viewed his conscription into the army as an opportunity or an undesired obligation, he went. It is quite likely that Kane was aware of the draft riots that roiled New York City two weeks before. In that unfortunate event the poor whites of Gotham, particularly the Irish, took out their frustrations on African American men, women, and children of the city, who they perceived as the cause of the war. The 30-year old river boat steward enlisted on July 31, 1863, and mustered into service a week later at Camp William Penn in Philadelphia. His officers must have noticed potential in the newly drafted soldier, because within a month after enlisting he received promotion to corporal. Kane’s officers’ trust was apparently well placed, as he fulfilled his commitment, demonstrated by his continual presence in the ranks. He fortunately survived the fighting at Petersburg on June 15, 1864, unscathed, as well as later duty in the trenches at the “Cockade City.”

Called upon to participate in the lead attack at New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, the 6th USCI followed closely behind the 4th. The Confederates seemingly targeted the white officer corps, as that group suffered about 36% casualties in the 6th USCI. In many cases non-commissioned officers like Kane stepped up and led the enlisted men who looked to them for direction. During the fury of the battle Sgt. Major Thomas Hawkins and 1st Sgt. Alexander Kelly saved the regimental and national colors of the 6th. Those two men later received the Medal of Honor for their courage, as did white officer Lt. Nathan Edgerton. Amidst the terror and confusion of battle, Kane received a wound in the leg. Although he received medical care at Balfour Hospital at Portsmouth, Virginia, Kane was unable to recover and passed away on October 13. Among the personal effects inventoried at the time of Kane’s death was a testament, a finger ring, two postage stamps, three pocket books, and five dollars in Iowa state currency. What ultimately became of these items is unknown.

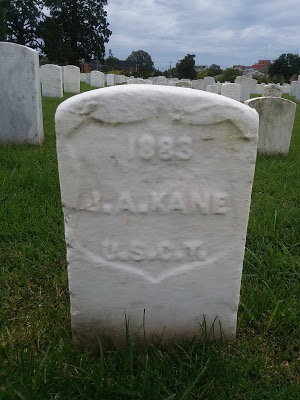

Black statesman Nelson Mandela once said that, “Courage is not the absence of fear, but the triumph over it. The brave man is not he who does not feel afraid, but he who conquers that fear.” Corp. James A. Kane answered his country’s call to arms, went to war, and fulfilled his duty, ultimately giving his life as a sacrifice for the promise of a more perfect Union. We acknowledge his service and pay respect to him and his final resting place at Hampton National Cemetery. Salute!