Historically speaking, some elections are more important than others. However, it is difficult to dispute the significance of the presidential election of 1864. Much was on the line. Many Confederate hopes rested on a McClellan victory, while the majority of Federal soldiers saw Lincoln’s reelection as the surest route to continued prosecution of the war and ultimate victory.

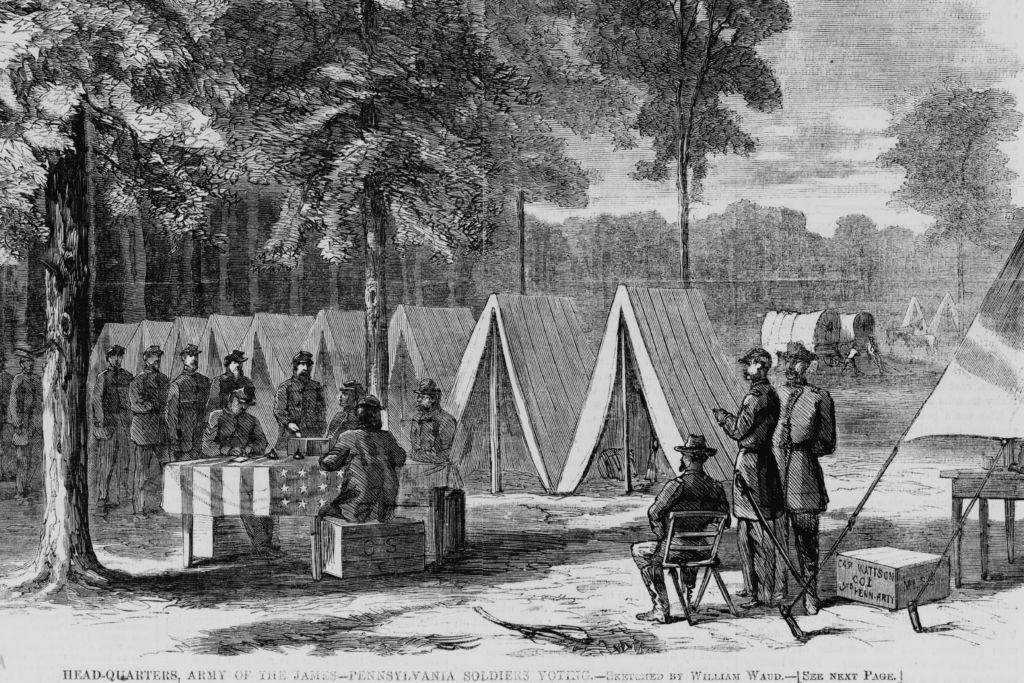

Pennsylvania soldiers in the Army of the James apparently voted early in the field as this woodcut published in the October 29, 1864, edition of Harper’s Weekly indicates.

Some states allowed their citizens soldiers to vote while in the field, others did not. Some states made allowances for a portion of their soldiers to come home on furlough and vote, while others did not. One state that did allow its fighting men to vote in the field was Ohio.

Ohio was also one of the few states that allowed some men of African descent to vote. Despite the state’s 1802 constitution that limited voting to White men, political shifts, court case precedent, and changes in some citizens’ sentiments during the mid-nineteenth century, led to limited franchise opportunities for African American men. Those males who met the voting age requirement and were determined to be more White than Black, often participated at the polls. It appears that decisions on who was “more White than Black” came from local election officials. Those townships who saw the value of accepting votes from men of African descent allowed it, while others did not.

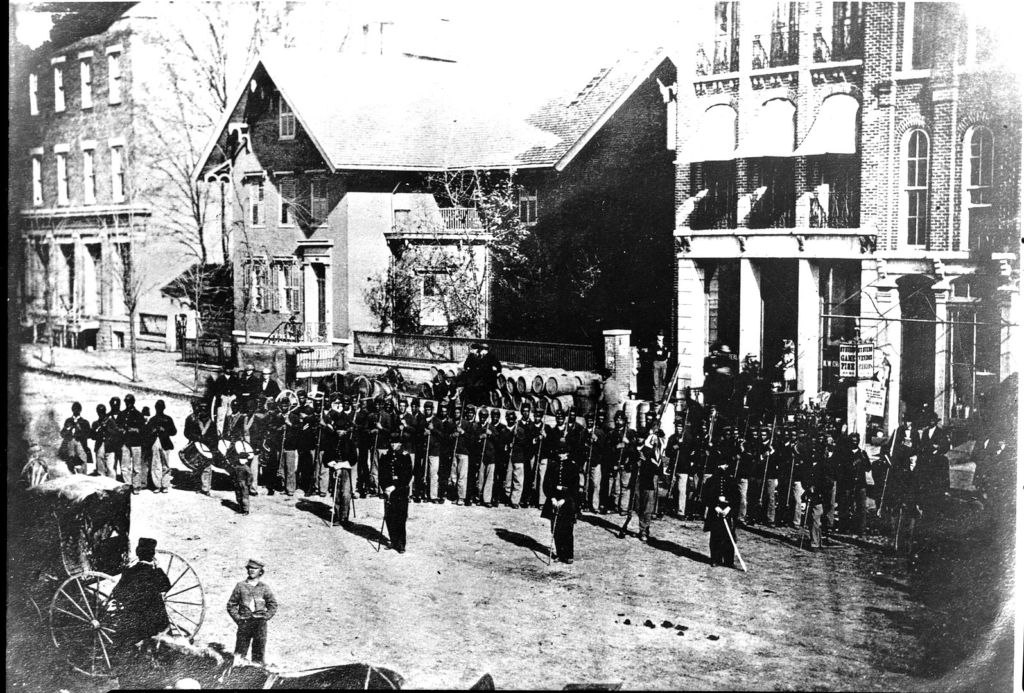

Image of a company of the 127th Ohio Infantry (later redesignated the 5th United States Colored Infantry) in Delaware, Ohio. Courtesy of the Ohio History Center.

Recruited from all sections of Ohio, the 5th United States Colored Infantry mustered into United States Service as the Buckeye State’s first Black regiment in 1863. Made up primarily of free men of color, who were born free, self-emancipated, or received manumissions from former enslavers and then migrated to Ohio, these recruits initially trained at Camp Delaware, north of state capital city of Columbus. Although the 5th USCI skirmished some while participating in raids in northeastern North Carolina in late 1863, and on the James/York River peninsula in the early spring of 1864, their first true taste of combat came on June 15, 1864 at Petersburg. During the opening actions of the Petersburg Campaign, as part of Gen. Edward Hinks’ Division of the Eighteenth Corps, the 5th USCI performed well at Baylor’s Farm that morning and along the original Dimmock Line of Confederate defenses later that evening, capturing several fortified positions. In doing so, the regiment sustained only limited casualties and gained valuable experience under fire.

As the 5th USCI transitioned to trench warfare at Petersburg in late June, July, and August 1864, their experience proved trying to the enlisted men and deadly to the officers. Two officers fell to sniper shots, some men received wounds from artillery shells, and of course, sickness was ever-present. In addition, while the Confederates tended to relax their firing at White Federal units across no-man’s-land, they often harassed Black regiments unsparingly. Reassigned to Deep Bottom landing on the James River at the end of August, the 5th USCI worked on strengthening the defenses there and picketing the area against nearby Confederates.

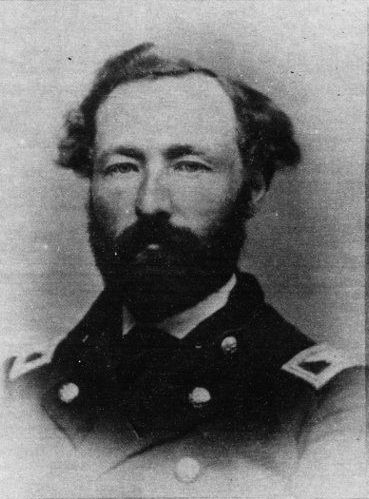

Col. Alonzo Draper led the brigade consisting of the 5th, 36th, and 38th United States Colored Infantry regiments at the Battle of New Market Heights. Image in the public domain.

At the Battle of New Market Heights, on September 29, 1864, the 5th USCI served in a brigade with the 36th and 38th USCI regiments. Commanded by Col. Alonzo Draper, the brigade fought in Brig. Gen. Charles Jackson Paine’s Third Division of the Eighteenth Corps, Army of the James. That morning, Draper’s Brigade received orders to follow the primary assault of Col. Stephen Duncan’s Brigade (4th and 6th USCI) directed at the Confederate defenses south of the New Market Road, which led to Richmond. After witnessing Duncan’s Brigade lose over half of its strength in the initial assault, Draper’s Brigade formed in column of regiments with the 5th USCI leading it and attacked over the same ground. They, too, took heavy casualties, but through strong noncommissioned officer leadership after many of the regimental White officers had suffered wounds, Draper’s Brigade rallied and broke though the famous Texas Brigade’s earthworks, driving off the defenders.

According to historian Versalle Washington, “Leading the charge of the 5th USCT into the rebel works fell to Lieutenant Joseph Scroggs’s Company H. After Lieutenant Colonel Shurtleff fell wounded, Lieutenant Scoggs’s men surged ahead. As they neared the works, Scoggs lost Color Sergeant George Steele, the regimental color bearer, and his orderly sergeant, William Strawder, was wounded in the neck. Orderly Sergeant Strawder, blood streaming from his wound refused to go to the rear for aid and soon joined his commander in the Confederate position.” Unfortunately, later in the day, when the Confederates fell back to Fort Gilmer, the 5th USCI again answered the call and attacked that fortified position losing additional casualties.

Among the 14 Black men who received the Medal of Honor for their heroism that day, four were from the 5th USCI: 1st Sgt. Powhatan Beaty, Co. G; 1st Sgt. James Bronson, Co. D; Sgt. Maj. Milton Holland, Co. C; and 1st Sgt. Robert Pinn, Co. I.

After New Market Heights and Fort Gilmer, the 5th USCI participated in the October 27, 1864, Federal offensive in conjunction with the Tenth Corps near Darbytown Road. Limited action that day resulted in about seven casualties for the regiment’s soldiers and officers. The 1st and 22nd USCI suffered significantly more.

As the presidential election neared, few other things were on the soldiers’ minds. However, as African American correspondent for the Philadelphia Press, Thomas Morris Chester, reported, “The election, so far as I saw and was able to learn, passed off in a very orderly manner.”

Apparently some controversy did develop about some of the Black soldiers of the 5th USCI voting. Correspondent Chester reported: “The voting of the 5th United States Colored Troops, who came from Ohio, was a little amusing, and attracted much attention from the McClellan men on the other side of the line. The supporters of Little Mac were gathered together in quite a crowd opposite the place of election of the 5th [USCI]; and it is more than probable they would have come over and given expression to their choice had it not been for the extensive line of armed men to prevent their indulging, in any such luxury. The colored men in front of the 5th were particularly vigilant lest those who had been so intently watching them from early morn should claim their ‘constitutional privilege’ and avail themselves of the opportunity to express their admiration for McClellan.”

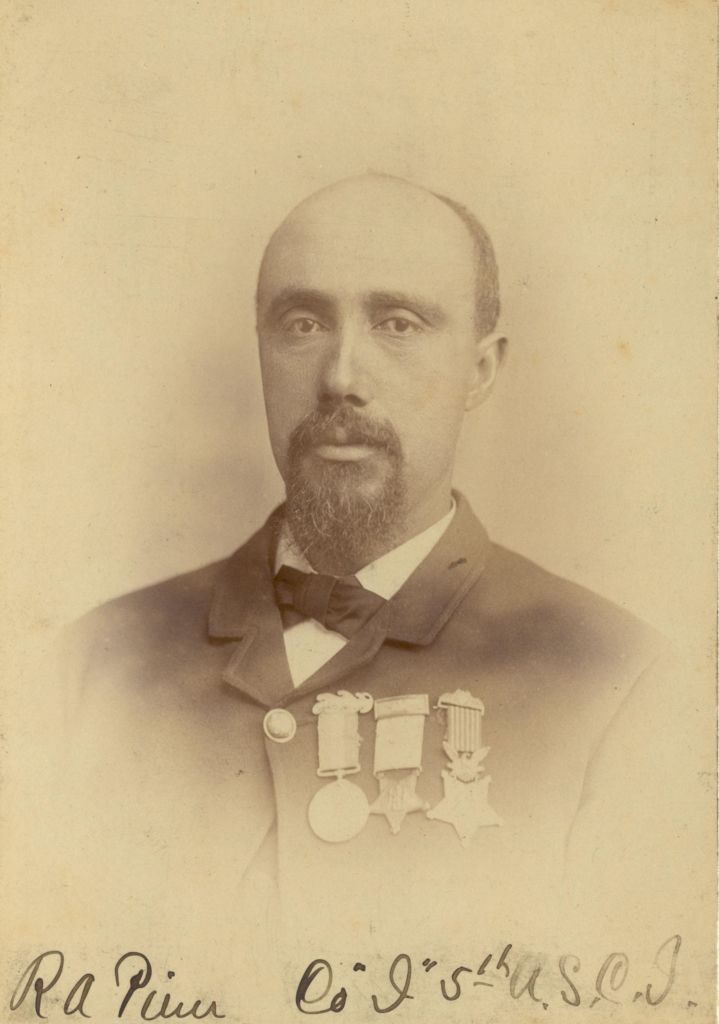

1st Sgt. Robert A. Pinn, 5th USCI, shown here in a postwar photograph, probably voted in the 1864 presidential election. Note his Medal of Honor, Butler Medal, and G.A.R. medal. Image in the public domain.

It is likely that three of the Medal of Honor recipients from the 5th USCI voted in the election. 1st Sgt. Powhatan Beaty, 1st Sgt. James Bronson, and 1st Sgt. Robert Pinn were all above the legal voting age of 21 and of were of mixed race ancestry. Sgt. Maj. Milton Holland, also mixed race, missed the eligible voting age by a year, although he may have voted, too.

Age or complexion may not have mattered to some of the soldiers. According to a story in the December 7, 1864, edition of Oberlin, Ohio’s Lorain County News, at least one soldier voter in the 5th USCI was questioned as to his eligibility, probably due to his dark complexion. The soldier, an unnamed orderly sergeant, “pointed to an ugly scar on his throat, saying that ‘that had earned him the right to vote anywhere.’” Historian Versalle Washington credits the quote to 1st Sgt. William Strawder, who received a neck wound at New Market Heights. If so, Stawder’s enlistment records indicate that he was too young and probably not of mixed race ancestry to have legally voted. Strawder, a barber, who was born in Lancaster, Ohio, was only 18 years old when he enlisted on June 29, 1863, and his complexion at his enlistment was noted as Black. If it was Sgt. Strawder, perhaps he felt that his service to a nation that did not yet technically consider him a citizen, and his near death experience on the battlefield, outweighed such qualification details. Regardless, correspondent Chester reported that the 5th USCI cast 194 votes for Lincoln, and 0 for McClellan.

The right to vote without the hair-splitting distinctions of racial ancestry is one of the things that the men of the 5th USCI were fighting for. Holding the right of suffrage, a key element of citizenship, was a step closer toward social and political equality, and realizing the claims of the Declaration of Independence and guarantees of the Constitution. It would be four more years until before the states ratified an amendment to the Constitution that provided citizenship to all African Americans, and six more years before the Fifteenth Amendment gave the elective franchise to Black men. However, the soldiers of the 5th USCI, and all United States Colored Troops, could claim proudly that their participation in the Civil War helped bring about these positive changes that moved the United States in the direction toward a more perfect Union.