We are fortunate that several United States Colored Troops (USCT) soldiers chose to write from their camps to newspapers who were supportive of their efforts, relating their experiences in the Union army during the Civil War. Without these public missives, we would know far less about numerous aspects of their service. Newspapers like, The Anglo-African, the New Bedford Mercury, and particularly the Christian Recorder—a sheet published in Philadelphia by the African Methodist Episcopal Church—all printed soldiers’ letters.

Quartermaster Sgt. James H. Payne of the 27th United States Colored Infantry (USCI), a regiment raised in Ohio, wrote to the Christian Recorder on December 21, 1864, telling the brief biography of Lydia Penny, the wife of a 5th USCI (also recruited in Ohio) soldier’s wife who ministered to the wounded in the wake of the Battle of New Market Heights. The Christian Recorder printed Payne’s letter in their January 7, 1865 issue.

Lydia Penny probably told Payne her story after the formation of the XXV Corps in early December 1864. Previously, the 27th USCI was in the IX Corps of the Army of the Potomac, and the 5th USCI was in the XVIII Corps, part of the Army of the James. While in separate armies, these two regiments did not serve together. However, after the creation of the XXV Corps, the USCT division in the IX Corps transferred to the Army of the James.

Surviving historical records corroborate details of Lydia Penny’s story. Sgt. Payne’s service records confirm that he indeed served at that rank in the 27th USCI. Payne was born just across the Ohio River from the Buckeye State in Mason County, Kentucky. His records indicate that he was free before April 19, 1861, but do not state whether he was born a free man or if he emancipated himself. He was apparently living before and during the early part of the Civil War in Wyandot County, Ohio, where he enlisted on March 5, 1864.

In his letter to the Christian Recorder, Payne (also sometimes spelled Pain in his records) explains that Lydia Penny, who he referred to as “our very worthy and eminent sister and mother in the army,” was born enslaved in 1814 in Blount County, Tennessee. Penny labored for her East Tennessee enslaver as a cook. Unfortunately, her situation was like that of so many other enslaved women. Payne related that “she was at the time only a girl; but . . . subsequently became the mother of children whose companionship she had long been deprived of through slavery, and that she was left a widow to suffer the torments of cruel oppression.”

From those comments, one can infer that Lydia’s children were either sold from her or rented away, leaving her unable to see and mother them. Lydia herself became a victim of the internal slave trade when a German butcher in faraway Memphis purchased her. After “a falling-out with her Dutch mistress,” Lydia informed her enslavers that she intended to run away. She successfully fled and hid among friends in Memphis until the Union army occupied the city, probably during the summer of 1862. Lydia eventually made her way into the Union army’s lines and became a cook for the soldiers. While fulfilling that role, “and having no one in particular to befriend or protect her, prudence dictated the propriety of making selection of a companion.” Traveling with the Union army in Memphis was Thomas Penny, a Black man, who was working as a servant in a three-month White regiment.

Payne informed the Christian Recorder’s readers that Thomas Penny was “a native of Pennsylvania.” After the regiment’s term of service was up, Thomas and Lydia traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, where Thomas enlisted in the 5th USCI, on July 10, 1863. Thomas Penny’s service records state that he was born in Beaver, Pennsylvania, and signed up at age 47, which made him just a couple of years younger than Lydia. Payne wrote that Lydia “felt it to be her duty to go along with her husband, not merely on account of the love she had for him, but for also the love which she had for her country—that the cause which nerved the soldiers to pour out their life-blood was her cause, and that of her race….”

According to Sgt. Payne, Lydia Penny was known by the USCT soldiers as “’the mother of the army.’” Payne claimed that “Sister Penny . . . is not tired of service, nor does she think of leaving the field until the last gun is fired and peace declared, and every slave is freed from captivity.” Payne provided a vivid practical example of the invaluable service Penny provided to the USCT soldiers: “Many of our officers and men who were wounded at the battle of Deep Bottom [New Market Heights]* will never forget the kind deeds of Sister Lydia Penny, who went among them and administered to their wants as they lay weltering in their blood on the James River, near Jones’ Landing.”

Deep Bottom Landing on the James River. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress

There, Lydia Penny was, “the only woman present, like an angel from above, giving words of cheer, and doing all in her power to relieve the suffering of the wounded and dying.” As a comforter, “Sister Penny was seen, like a ministering angel, or one of those holy women who in primitive days administered to Christ and his apostles. She gave them water to drink and bread to eat, and assisted the surgeons in dressing their wounds.”

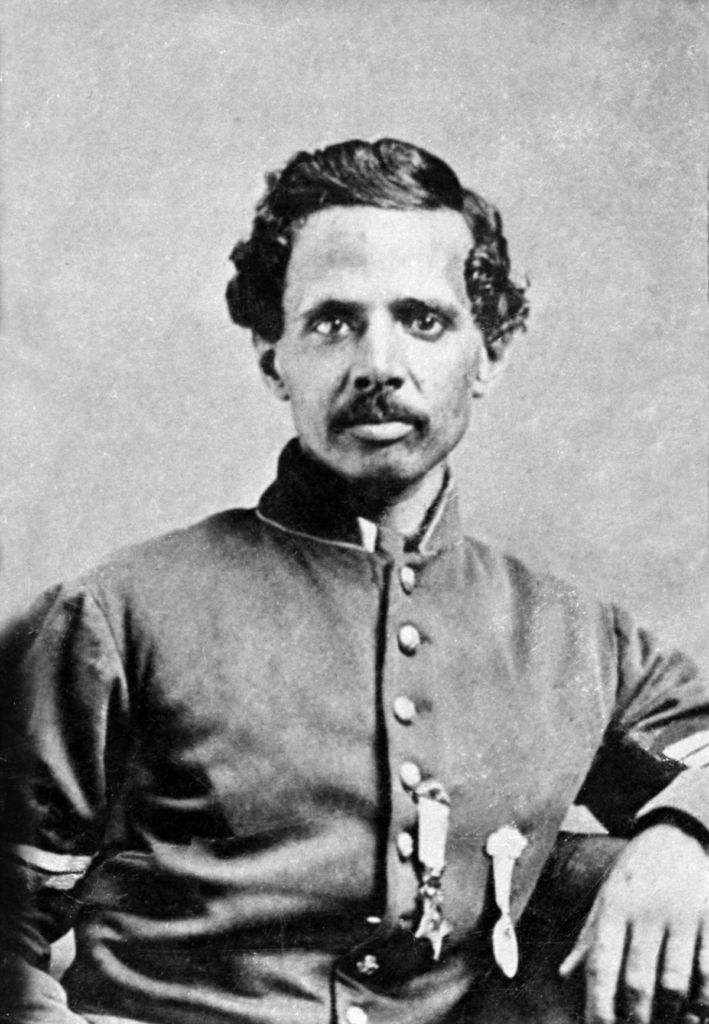

1st Sgt. Powhatan Beaty served in the 5th USCI with Pvt. Thomas Penny and received the Medal of Honor for his heroism at the Battle of New Market Heights. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As the wounded USCTs were loaded onto hospital transports that conveyed them down the James River to Union hospitals at Fort Monroe and Portsmouth, Virginia, “she left her tent and all behind and went on board the boats to minister to their comfort.” And when the wounded “were delivered into the hands of careful nurses, Sister Penny returned to her tent, where she waits to administer to the wants of the afflicted soldier.”

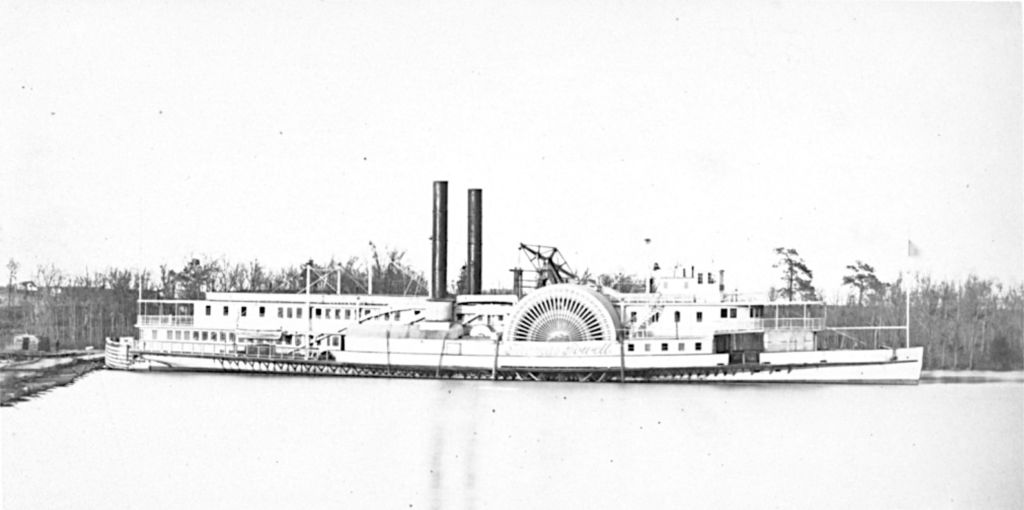

Hospital boats like the Thomas Powell, shown above, transported the New Market Heights wounded USCTs to hospitals. Image in the public domain.

It is quite probable that we would never know about Lydia Penny’s story and her compassionate efforts on behalf of the USCTs without Payne sharing it through the pages of the Christian Recorder. Here was a woman, who bravely joined her soldier husband in the army, risking her health and sacrificing her comfort for a better future; a future without slavery, and with the hope for liberty, equality, and citizenship in the United States.

Thomas Penny’s service records show he mustered out with the 5th USCI on September 20, 1865 at Carolina City, North Carolina. Lydia Penny appears in the 1870 census in Cincinnati, Ohio’s 14th Ward, as 56 years old and living in a boarding house without Thomas. It is possible that Thomas Penny died between the end of the war and the recording of the 1870 census. Lydia’s birthplace—noted as Blount County, Tennessee in Sgt. Payne’s letter—was Virginia. The 1870 census also indicated that Lydia could not read or write. Sister Penny also appears in Cincinnati’s 1875 and 1888 city directories. In 1875, Lydia worked as a milliner, and in 1888, cook was her given occupation. Lydia Penny lived at least until 1890 when she filed for a pension for her husband’s service in the 5th USCI. However, after that, she disappears from the historical record.

Just like the USCT soldiers she aided, we honor and remember Sister Lydia Penny, and all the other Black women who provided medical aid, encouragement, comfort, and service to the United States army during the Civil War.

Thousands of Black women served in various capacities for the United States military during the Civil War. Unfortunately, their stories often go untold. Cropped image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

*Edwin S. Redkey, the editor of A Grand Army of Black Men, in which Sgt. Payne’s Christian Recorder letter appears, interpreted Payne’s mention of the “battle of Deep Bottom” as the First Battle of Deep Bottom, noting the date “[July 27, 1864].” However, no USCT regiments participated in the First Battle of Deep Bottom. Brig. Gen. William Birney’s USCT brigade participated in the Second Battle of Deep Bottom in August 1864, but the 5th USCI, whom Lydia Penny served with, was not in that brigade. Sgt. Payne’s mention of the “battle of Deep Bottom” most assuredly refers to the Battle of New Market Heights (September 29, 1864), also sometimes referred to in military records as the Battle of Deep Bottom. The 5th USCI played a conspicuous part in the Battle of New Market Heights, where they endured significant casualties and four of their soldiers received the Medal of Honor for courageous actions.