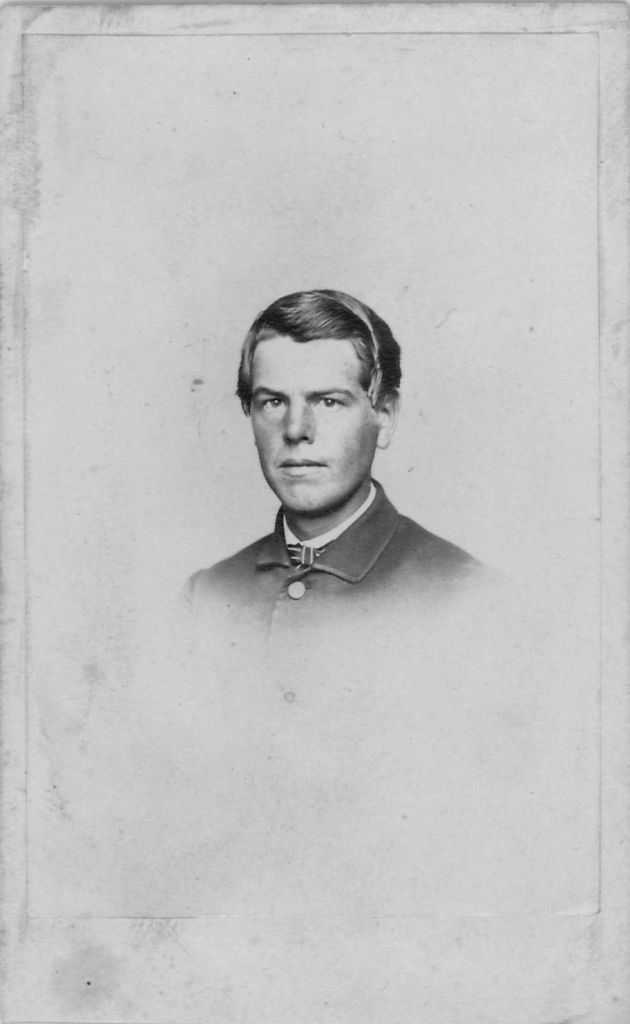

Image courtesy of Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier

Lt. William W. Moore was only 23 or 24 years old when his life ended violently on September 29, 1864, at the Battle of New Market Heights.

Serving as second lieutenant in Company C of the 38th United States Colored Infantry (USCI), Moore received a fatal wound in the desperate charge against the Confederate earthworks defended by the famous Texas Brigade just southeast of Richmond. Little is known of Moore other than what is provided in his service records and other official documents. His youthful image, though, survives among those kept and protected in the collections at Pamplin Historical Park and the National Museum of the Civil War Soldier.

Moore began his Civil War military career when he enlisted in August 1862, as a private in Company B of the 50th New York Volunteer Engineers. While with this distinguished unit, Moore first received a promotion to artificer on October 7, 1862, and then a couple of weeks later to corporal. He apparently served well in that role before receiving a promotion to second lieutenant when he transferred to Company C, 38th USCI, on January 26, 1864.

Few issues better illustrate the racism that pervaded America in the mid-nineteenth century than the U.S. Army’s unwillingness to allow black commissioned officers to lead black regiments. At that time it was widely believed that African American recruits required strong capable white officers in command to make black men effective fighters. However, despite this prejudicial measure, the army did establish a system that attempted to ensure the best white candidates received appointments to these positions.

In most instances, in order to obtain a commission with a United States Colored Troop regiment, candidates like Moore had to undergo and pass an examination. At locations like Washington D.C., Cincinnati, and St. Louis, those seeking officer roles with black regiments went before a review board to test their knowledge and abilities, and weigh their prejudices. The purpose for the rigorous examination was to both weed out those men who were only looking to advance for the sake of rank and or pay, and to try to identify and then incorporate those competent leaders who had genuine interests in advancing African Americans’ abilities as enlisted men and non-commissioned officers.

Lt. Moore, first stationed in the Old Dominion with the 50th New York Engineers, and then appointed to a black regiment partly raised and serving in Virginia, likely faced the Washington D.C. review board for his examination. To assist those men who had promise but perhaps not the strongest educational backgrounds pass their board examinations, a free officer’s school was set up in Philadelphia, too. It is unknown whether Moore took advantage of the officer’s school opportunity.

Naturally, despite the army’s attempts to limit the number of incompetent and abusive white officers, some made it through the screening process. However, the majority of the men, like Moore, took their responsibilities seriously and fulfilled their duties, many giving the last full measure of devotion along with the men they led.