When attempting to tell the life story of Civil War soldiers, limited sources of information often prove to be the greatest challenge. While the information contained within their compiled military service records can provide some fantastic insights, most of that information only covers the time period they were in service. Other sources, such as census records, city directories, and governmental records are extremely helpful when they are available. However, searching for information about men who served in the United States Colored Troops (USCT) can be especially difficult due to a whole host of reasons that they often faced in that era as enslaved men or free men of color. The level of difficulty increases if the soldier did not survive the war, which of course eliminates the chance that they produced any records after their service.

An excellent subject example is Pvt. Benjamin Davis, who served in Company E of the 6th United States Colored Infantry (USCI). Important information that otherwise might be difficult to find appears in Pvt. Davis’s service records. Knowing that Davis was below average height—standing a mere five feet two inches tall—, that he was also in the approximate average age range for Civil War soldiers at 28 years old, and that he worked as a barber, was born in Philadelphia, had a “black” complexion, and enlisted on August 15, 1863, all provide significant puzzle pieces of biographical information.

Davis’s service records also indicate that he received a promotion to corporal at some unspecified point, but they also clearly show that he lost his non-commissioned officer status on December 14, 1863, and returned to the rank of private, “for leaving his work and returning to camp without permission.” What type of work Davis left undone goes untold, but he apparently later received an assignment to serve on January 1, 1864, as a nurse in the regimental hospital. Despite Davis’s reduction in rank, he was always present for duty. He appears to have survived the scouting missions on the York/James River peninsula in the spring of 1864, the fights on June 15, 1864 at Petersburg, and duty there in the trenches unscathed.

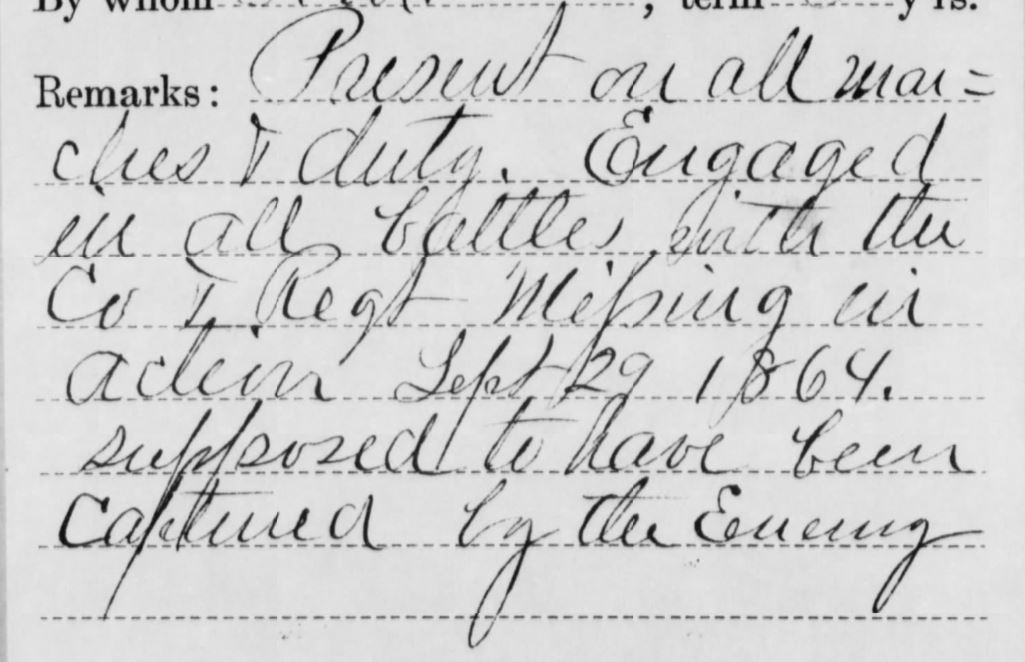

Pvt. Benjamin Davis’s compiled military service records note in a couple of places that he went missing in action at the Battle of New Market Heights on September 29, 1864, (Fold3.com)

Two pieces of information in Pvt. Davis’s service records show that he went missing at the Battle of New Market Heights. His September/October card states: “Missing in action Since Sept 29/64.” The other is a letter from attorney E. O. Jackson of Philadelphia and dated March 24, 1865. In it Jackson states that Pvt. Davis’s father wanted to know if “his son is alive or dead and iff a live wheer a letter will reach him.” Also the letter mentions that Davis’s father had heard that his son was dead, and if so, “inform me wheer he died[,] of what diseas[,] and the date of his death.”

Formerly a major serving in the 14th New Hampshire Infantry, Col. Samuel Duncan commanded the brigade that included the 4th and 6th USCI at New Market Heights. (Library of Congress)

Sources from the Battle of New Market Heights indicate that a few of the men in Col. Samuel Duncan’s Brigade—comprised of the 4th and 6th USCI—who made the initial attack in the battle somehow made their way through a hail of artillery and entrenched rifle fire, through two lines of abatis, across marshy ground, and into the earthworks of the Texas brigade. The Lone Star State troops were incensed to find they were fighting Black men. Some defenders felt that Butler’s choice to attack with Black troops was “like flaunting a red flag before a mad bull.” One Texan recalled that “the word passed along the line that they were negroes and to give them lead. Every fellow shot with as much precision as if they were at a shooting match.”

Lt. Joseph Goulding, Co. K., 6th USCI, remembered the unfolding deadly scene at New Market Heights: “With shouts and cries, with deep drawn breath and gasps and choking heart-throbs we plunge on and on, men dropping suddenly or thrown whirling or doubled up as they were struck. Now we reach the brook [Four Mile Creek] and are tearing our way through the brush. What wild music the bullets sing as we force our way along! ‘Keep on boys.’ My God, see them reel and stagger, and yet still keep coming on. The dense masses of the rebels, their yellow works, are in plain sight; we hear their shouts and cheers, their pitiless, incessant, withering volleys. Surging up to the parapet, our men leap the low, newly made lines and black and white meet, hand to hand, no longer as master and slave.”

Despite this brief measure of success, the assault of 750 men in the two regiments was not enough to push out about 1,800 entrenched and well supported Texans. Without immediate reinforcements, Duncan’s small brigade had to fall back after losing over half of their men and displaying incredible acts of heroism that eventually earned six soldiers Medals of Honor; each regiment receiving three.

If Davis’s service record information served as the only available source, we would probably not have definitive proof that he was among those Black soldiers who breeched the Texas Brigade earthworks. Fortunately, Davis’s father, Robert, pursed a pension for the loss of his son to the United States army. In doing so, a conflict in information arose that produced a significant amount investigative paperwork and thus additional information about Pvt. Davis.

A plethora of information in Davis’s pension file fills in many of his biographical gaps. Included in the file are statements from Mary Williamson, who was the wife of Benjamin Davis and the mother of their son, Jerome. Mary answered numerous questions posed by the pension agents attempting to sort through why Davis’s father filed for a guardian’s pension and not her. They were particularly interested in her relationship with Davis and the birthdate of Jerome. She explained that Jerome was born on April 17, 1863. Mary stated that Benjamin was drafted that same year in August. While Pvt. Davis’s service records do not state that he was a draftee, many men in the 6th USCI were. Mary also said that Benjamin went off to war in 1862 as an officer’s servant for a Capt. Ernestine in a 90-day Pennsylvania regiment; she did not know the regimental number.

According to Mary, not long after Benjamin returned home from his three months of service, he traveled to Massachusetts over a three day period in an attempt to enlist in the 54th Infantry regiment. But Davis was rejected due to a stab wound on his right side from his youth. Mary stated that she took Jerome to his grandfather Robert Davis’s home when he was about seven or eight months old per the request of Benjamin as Benjamin knew Mary had to work to support herself and did not think she could properly take care of Jerome. Robert Davis raised Jerome and Mary remarried in 1865 after learning of Benjamin’s death. Mary even told the investigator the places that Benjamin worked as a barber and bar tender before enlisting.

When asked what became of Benjamin, Mary said that she received a letter from one of Benjamin’s comrades “that he was captured at Deep Bottom, Va, and was shot and killed while a prisoner.” Another comrade gave her the same information when he came home from the war. She provided all of this information was in 1884, almost 20 years after the war, but it is clear that her memory was sharp and her answers can be corroborated with other sources.

What apparently caused the later investigation was Robert Davis’s statement in his original claim on August 18, 1865, that Benjamin “left no widow or child surviving.” Robert later explained that he said that because Mary did not have a marriage certificate for her union with Benjamin and thus could not prove she was the lawful widow of Benjamin. Robert explained that as he was serving as the guardian of Jerome and Mary had remarried in 1865, he was due Benjamin’s pension. From Robert Davis’s testimony we also learn that Benjamin Davis was born on February 15, 1835. Additionally, Robert stated that “In 1865, I can’t remember the month, one of the soldiers of my sons company, came home and said he was taken prisoner the same time my son was taken prisoner, and killed. . . .”

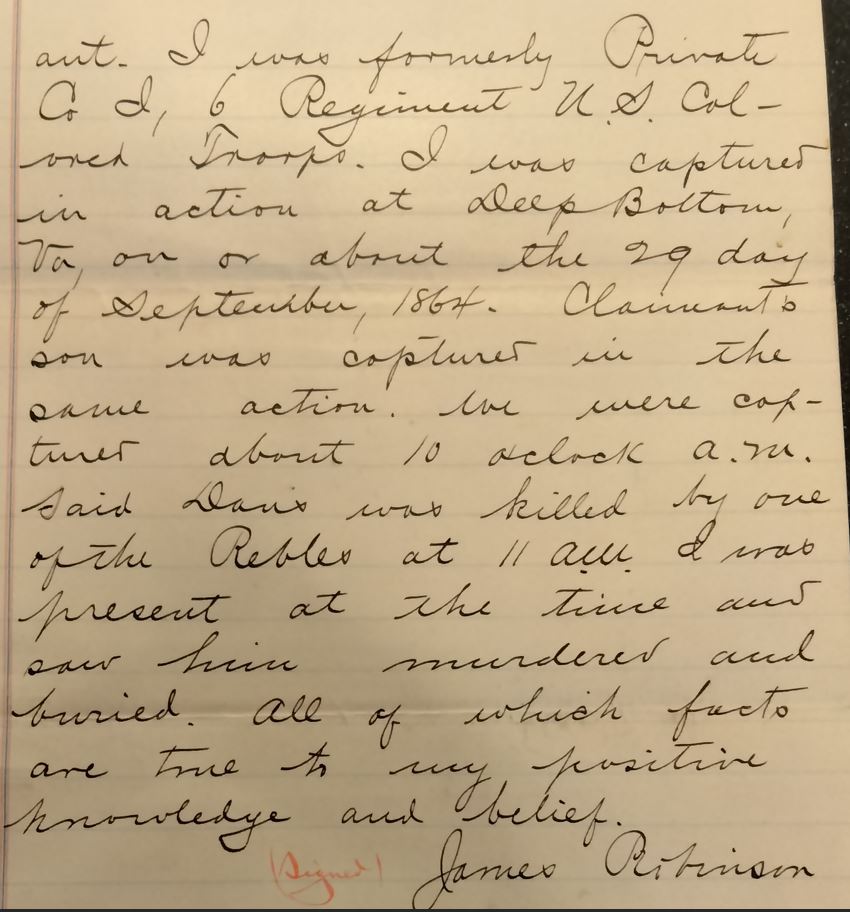

Pvt. James Robinson, a 6th USCI comrade of Davis’s, who was also captured at New Market Heights, witnessed a Confederate soldier kill Davis. (National Archives and Records Administration)

Another statement in the original claim came from James Robinson, a former 6th USCI comrade of Benjamin’s, who served in Company I. Robinson swore that “I was captured in action at Deep Bottom, Va, on or about the 29 day of September, 1864. Claimant son [Benjamin Davis] was captured in the same action. We were captured about 10 o’clock a.m. Said Davis was killed by one of the Rebels at 11 a.m. I was present at the time and saw him murdered and buried.” Robinson’s service records corroborate his stated regiment and company and they note that it was believed that he was killed at the Battle of New Market Heights, but he eventually returned to his company at an unspecified date.

Robert and Sarah Davis appear in the 1870 census. In the household as he testified was Jerome Davis, listed as eight years old. A decade later, 19-year-old Jerome was still living with his grandparents, who were then in their sixties. The 1900 census lists Jerome Davis as a 37-year-old working in “Day Labor” and married to Anna, who was five years older. No children are listed. A death record notes that Jerome died on March 30, 1906, at age 42 as a widower.

According to another document in Pvt. Davis’s pension file, he apparently refused to perform some unspecified labor for his captors almost immediately after falling into their hands. This act of defiance, along with other details of his life story and his service and sacrifice for the United States as a Black soldier would have been lost to history were it not for the evidence that these records hold.